0000-0003-0329-2531

0000-0003-0329-2531  nayibisdm@gmail.com

nayibisdm@gmail.comAlfredo González Marrero1

0000-0001-7920-2673

0000-0001-7920-2673  alfredoglezm1995@gmail.com

alfredoglezm1995@gmail.comMarielys Moore Pedroso1

0000-0003-3479-872X

0000-0003-3479-872X  m.moorepedroso@unah.edu.cu

m.moorepedroso@unah.edu.cu

Cooperativismo y Desarrollo, September-December 2025; 13(3), e932

Translated from the original in Spanish

Original article

Social manifestations of risks to equity in agricultural work in Cuban cooperatives

Manifestaciones sociales de riesgos para la equidad del trabajo agrario en cooperativas cubanas

Manifestações sociais de riscos para a equidade do trabalho agrícola nas cooperativas cubanas

Nayibis Díaz Machado1  0000-0003-0329-2531

0000-0003-0329-2531  nayibisdm@gmail.com

nayibisdm@gmail.com

Alfredo González Marrero1  0000-0001-7920-2673

0000-0001-7920-2673  alfredoglezm1995@gmail.com

alfredoglezm1995@gmail.com

Marielys Moore Pedroso1  0000-0003-3479-872X

0000-0003-3479-872X  m.moorepedroso@unah.edu.cu

m.moorepedroso@unah.edu.cu

1 Agrarian University of Havana "Fructuoso Rodríguez Pérez". Mayabeque, Cuba.

Received: 19/08/2025

Accepted: 16/12/2025

ABSTRACT

This exploratory sociological research aimed to identify social manifestations of risks to agricultural labor equity in the context of Credit and Service Cooperatives in San José de las Lajas, Mayabeque province. In the selected cooperatives and related organizations, in-depth interviews were conducted with leading producers, scientific observation of assembly dynamics was carried out, and content analysis was performed on interviews from previous studies related to these contexts. Among the risks to agricultural labor equity, the following were identified: the almost exclusive perception of farm owners as the actors in agricultural labor, low visibility of hired workers, short-term commercial interest among young producers, informal hiring and evasion of social security taxes, women's limited understanding of the benefits of joining a cooperative, the perception of legal proceedings with the Department of Agriculture as an obstacle, dissatisfaction with the state's failure to pay for production, and other risks with strong implications for agricultural work, its equity, and sustainability.

Keywords: cooperatives; equity; social risks; agricultural work.

RESUMEN

Esta investigación sociológica, con carácter exploratorio, tuvo por objetivo identificar manifestaciones sociales de riesgos para la equidad del trabajo agrario en el ámbito de las Cooperativas de Créditos y Servicios en San José de las Lajas, provincia Mayabeque. En las cooperativas seleccionadas y en organismos de relación, se aplicaron entrevistas en profundidad a productores líderes, observación científica a dinámicas de asambleas, análisis de contenido a entrevistas de estudios precedentes relativos a esos contextos. Entre los riesgos para la equidad del trabajo agrario, se identificaron: la percepción casi exclusiva de los poseedores de fincas como los actores del trabajo agrario, poca visibilidad de los trabajadores contratados, interés mercantil de corto plazo en los productores jóvenes, contratación informal y evasión del tributo por concepto de seguridad social, escasa noción en las féminas del beneficio de asociarse a la cooperativa, visión de obstáculo atribuida a la gestiones legales con la Dirección de la Agricultura, disgusto por el impago estatal a producciones, y otros riesgos con fuertes implicaciones para el trabajo agrario, su equidad y sostenibilidad.

Palabras clave: cooperativas; equidad; riesgos sociales; trabajo agrario.

RESUMO

Esta investigação sociológica, de caráter exploratório, teve como objetivo identificar manifestações sociais de riscos para a equidade do trabalho agrícola no âmbito das Cooperativas de Crédito e Serviços em San José de las Lajas, província de Mayabeque. Nas cooperativas selecionadas e em organismos relacionados, foram realizadas entrevistas aprofundadas com produtores líderes, observação científica das dinâmicas das assembleias e análise de conteúdo de entrevistas de estudos anteriores relativos a esses contextos. Entre os riscos para a equidade do trabalho agrícola, foram identificados: a percepção quase exclusiva dos proprietários de fazendas como os atores do trabalho agrícola, pouca visibilidade dos trabalhadores contratados, interesse comercial de curto prazo nos jovens produtores, contratação informal e evasão do tributo de segurança social, pouca noção das mulheres sobre os benefícios de se associarem à cooperativa, visão de obstáculo atribuída às gestões legais com a Direção de Agricultura, descontentamento com o não pagamento do Estado às produções e outros riscos com fortes implicações para o trabalho agrícola, sua equidade e sustentabilidade.

Palavras-chave: cooperativas; equidade; riscos sociais; trabalho agrícola.

INTRODUCTION

Social science approaches to Cuban agricultural policy emphasize the importance of managing labor relations (Leyva Remón & Echevarría León, 2017). In this regard, resolving socioeconomic asymmetries, recognizing the diversity of demands for participation and consumption, and managing interests and conflicts are considered essential. These aspects value equity in productive relations as an end in itself and, at their core, equity in agricultural work as a basic condition for sustainable agricultural development.

In Cuba, agricultural cooperatives are considered to be in line with the constitutionally socialist system, but Credit and Service Cooperatives (CCS in Spanish) have been viewed as less socialized due to their historical basis of private land ownership. Without proper management, this can pose a challenge in terms of risks to labor equity due to concepts and practices rooted in these dynamics, which have the potential to generate inequalities in terms of opportunities and institutional treatment.

In the western province of Mayabeque, whose agricultural sector is strategic due to its contractual commitments with the country's capital, there is a strong cooperative sector. The most numerous are the CCS (Onei, 2022), a characteristic that is representative of the municipality of San José de las Lajas.

In this context, social studies are mainly subordinated to the agricultural sector, due to the complex of scientific institutions of this profile established in the territory, which includes the Agrarian University of Havana. As a result, research on sociological issues in agriculture, such as inequalities related to work, its determining factors, and the implications for the social actors involved in this activity and for its sustainability, is scarce or unsystematic.

This exploratory study identifies risks to equity, which may provide a basis for further interdisciplinary research in the agricultural sector. Similarly, it seeks to serve as a scientific alert to public policies regarding necessary changes in labor relations management, with an emphasis on the cooperative and non-state sectors.

Agricultural work in Cuba as a scientific subject has received little systematic attention, as sociological studies of agriculture have prioritized the impacts of policies, factors that favor or hinder them, transformations of the social actors involved, sustainability, and technologies (Díaz Machado, 2024; Nova González, 2022).

The category of work has been approached as an activity and process of human interaction with the natural and social environment to create the material and spiritual conditions that guarantee life in society, while reproducing that civilizational condition as a cultural expression, transmitting the experience to other generations (Izquierdo Quintana & Martín Romero, 2022; Martín Romero, 2020).

Despite the limited scientific visibility of work in the Cuban agricultural sector, frequent analyses of agricultural policy refer to issues of management and transformations in labor relations, as well as persistent equity gaps (Leyva Remón & Echevarría León, 2017).

In the context of this research, since the emergence of the CCS, each producer retained private ownership or management of the land on their farm, while credits and services for their economic activity were managed collectively. As their private foundations were considered by the government to be incompatible with socialism, they ceased to be a strategic priority from the late 1970s onwards, in comparison with the other two types of cooperatives existing in the country1.

The official narrative and policies of nationalization and collectivization led in the medium term to a drastic decline in the number of peasant farmers who owned and worked their own plots of land and, with this, to a weakening of the culture of agricultural work. State-owned enterprises became widespread in agriculture, with a majority of the workforce being salaried. The social structure, where small individual farmers or cooperatives had previously risen to prominence, was reconfigured in the early 1990s with workers, technicians, and state officials, with fixed remuneration and homogenized access to resources, plans, and results. This led to a symbolic reduction in the focus on work to the level of employment, mostly state-owned.

The transformations of the "Updating of the Cuban Economic and Social Model" since the first decade of the 2000s once again prioritized the growth of small individual farmers or cooperatives, given the low productivity of other economic organizations (García Álvarez, 2020; PCC, 2016), with land grants and measures in favor of the CCS. Many individuals and families moved towards these, but now as usufructuaries, with a symbolic universe distant from traditional peasant work.

In this context, agricultural work has been recognized as an activity involving the transformation, management, and production of land and its derivatives, from the roles of producer-administrator, family members involved in the dynamics, farm workers with formal or informal contracts, cooperative employees, and producer-workers (Díaz Machado, 2024; Díaz Machado et al., 2021; González Marrero et al., 2024). Emphasis has been placed on the need for public policies to focus more on equity, especially in organizations such as the CCS, where the sense of peasant identity is gradually weakening.

Economists and sociologists agree that equity should be understood as equality in terms of rights of access to opportunities, starting from unequal conditions (Espina Prieto & Echevarría León, 2020). This implies leveling out the initial disadvantages of some individuals compared to others, while deciphering cultural processes that legitimize inequalities and limit the realization of justice (Hidalgo López-Chávez, 2020).

This goal also requires going beyond the elimination of legal or formal barriers to create favorable conditions for the active and equitable participation of diverse social actors in all areas (Muñoz Subía & Pangol Lascano, 2021). Although this criterion focuses on gender relations, its vision that equity includes adopting policies to promote work-life balance and shared responsibility for tasks and activities is applicable to various settings.

In this regard, López Belloso et al. (2021) highlight the importance of recognizing, from a policy management perspective, that equal opportunities are not a static or definitive goal, but rather a continuous process that requires multi-stakeholder collaboration and measures in multiple instances.

These criteria, especially those of García Álvarez (2020), Echevarría León (2020), and Zabala Arguelles et al. (2022), provide key conceptual elements for research on equity in agricultural work. This is defined as: the institutional materialization of equal opportunities, rights, and starting conditions, supported by regulations and practical legal monitoring, for access to the resources and services necessary for work, as well as to the material and symbolic well-being generated and its costs, leveling out the objective disadvantages of individuals and groups in terms of territory, gender, generation, skin color, social origin, role, and economic entity where they are employed.

On the other hand, social risk has been theorized as uncertainty of foreseeable effects in unfavorable terms, generated by policies on social groups (Beck, 2002; Luhmann, 1992), but also attributed to conceptions, decisions, and behaviors toward those policies and toward power relations, emerging from the dissatisfaction of demands and expectations of the subjects to whom they are directed (Díaz Machado, 2024).

With regard to problems in the agricultural sector that may pose risks to labor equity, Cuban analysts, without explicitly using these categories, have highlighted realities such as the lack of agricultural experience or tradition among more than 70% of new cooperative members. This has been identified with greater emphasis since the beginning of this decade, when new producers (usufructuaries), facing economic and legal uncertainty, began to be guided by short-term profitability criteria, especially the younger ones, who were more like entrepreneurs than farmers in their relationships with employees on their farms (Arias Guevara & Leyva Remón, 2019).

With regard to these employees, there has also been a growth in legal informality and instability in many contracts, in order to evade paying taxes to the state. This has led to precariousness and the reproduction of the employer-subordinate relationship, which for decades has been attempted to be eradicated through the constitutionally socialist process in Cuba (Donéstevez Sánchez & Muñoz González, 2017; García Álvarez, 2020).

These theoretical contributions and study results make it easier to define risks to equity in agricultural work in the CCS sphere, such as: the foreseeable adverse effects attributed to concepts and practices in cooperatives and their politically related or governing entities for equal opportunities in terms of access to resources and basic services, participation and responsibilities, monetary income, and job sustainability, according to knowledge, skills, age, socio-structural background, geographical area, soil characteristics, gender, and form or type of economic management.

The introductory and theoretical elements presented above support, in summary, the objective of identifying social manifestations of risks to equity in agricultural work in the context of Credit and Service Cooperatives in San José de las Lajas, Mayabeque province.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The research was exploratory in nature, as it sought to highlight the presence of previously defined risks that have not yet been addressed in the provincial and national context. In this regard, it relied on methodological elements from the documentary study, based on the essential source found in previous and recent research, with different purposes but related to the object of this study.

It was designed as a case study, focusing on three CCSs in rural areas of the municipality of San José de las Lajas. These are named Nelson Fernández, René Orestes Reiné, and Camilo Cienfuegos. This selection was made due to the objective impossibility of covering the large number of cooperatives of this type existing in the locality (17), but also because of the characteristics of the exploratory study itself, which was designed for preliminary investigation of the phenomenon of scientific interest.

Among the methods used, the historical method stood out, as it made it easier to perceive, in the evolution of cooperativism and agricultural work, the factors that currently pose risks to equity. Closely related to the former, the analysis-synthesis provided a critical examination, in summary, of the theoretical foundations for defining equity in agricultural work and the risks to it.

Non-participatory scientific observation was carried out in members' meetings and in exchanges between the authors of this research and the boards of directors of the three selected CCSs.

In addition, in-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with leading producers, in line with the objective of the exploratory study, which required finding reference criteria from the agricultural workers themselves. They were given greater recognition by the other members of their respective CCSs, regardless of production results and the official institutional view.

Content analysis was applied to the results of two recent studies in local CCSs, one on the topic of agrarian cultural reproduction and the other on expressions of political culture that pose risks to agrarian policy objectives, both of which have already been referenced. Since these studies did not have the same objective as this exploratory study, a second reading allowed for the interpretation of expressions of risks to equity in agricultural work in the behaviors, conceptions, and organizational practices described by these previous studies, both in the organizations studied and in business, administrative, and other entities generally related to these cooperatives.

The analysis of documents also provided a general characterization of the three CCSs taken as case studies, all of which produce cow's milk in the first instance, but also various crops. This method also revealed the presence of certain risks related to age and gender.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The analysis was carried out on the basis of four essential manifestations of risks: those associated with the perceptions and practices of producers and cooperative members in general; those attributed to the conceptions and procedures of business, administrative, and formal relationship entities with cooperatives; those involved in the sociodemographic characteristics of cooperative members themselves; and those related to approaches expressed about these productive organizations by experts in the field.

With regard to producers and cooperative members in general, interviews with leaders and analysis of responses from interviewees in the previous study (Díaz Machado, 2024) revealed a growing interest in short-term commercial gain. This was particularly evident among producers in the role of administrators or landowners and among younger people, who engaged in the precarious exploitation of agricultural laborers, with little attachment to agricultural work itself, the future preservation of that work, natural resources, or the social security of the workers themselves.

Regarding these workers hired on farms, the perceptions of the producers interviewed boiled down to the fact that they were paid adequately for their work and that the non-payment of social security taxes was agreed upon with them. The prevailing view in this regard was that paying the government was a waste of money. In other words, a symbolic agreement was identified between producers and their hired workers, with a short-term view of the welfare of those employees.

There was a strong self-perception among land-owning producers that they were the actors in agricultural work, without associating this status with the workers hired on their farms, whose informal status implies job insecurity compared to other employees of the cooperative.

At the same time, among the most harmful concepts and practices for the work of CCSs compared to other entities, both currently and in the future, was the growing questioning by producers themselves of the usefulness of their organization, which reflected the self-perception of private actors in agricultural work.

In terms of specific risks to gender equality in CCSs, the interviews and observations did not reveal any limitations imposed by the cooperative, but rather the women's own decision not to formally join, arguing that they wanted to have more time for their personal and household chores and to perform other tasks to support the family economy. This was seen as an indicator of the need for greater awareness and training for women regarding opportunities for equitable economic growth.

In addition, a perception was identified among producers that equity in their work was being sought by the CCS boards of directors, but with significant limitations arising from external institutional treatment by entities of the Ministry of Agriculture (Minag) and the National Association of Small Farmers (Anap in Spanish) in the territory.

In exploring the risks attributed to the concepts and procedures of business and administrative entities and their formal relationship with cooperatives, producers highlighted the less equitable institutional treatment of CCS work compared to other forms of agricultural production, whether state-owned or non-. It was notable that, in this regard, hired agricultural workers were not visible as exponents of this cooperative work, which is at a disadvantage compared to that of other organizations.

What was made visible through observation of the assembly dynamics, expert opinions, and leading producers, linked the greater collective discontent with the state's failure to pay what had been contracted, the scarce and unequal distribution of resources and inputs between the CCS and productive organizations in the state sector, the delayed or absent response to problems and dissatisfactions that hinder work, and what they described as mistreatment received from Minag authorities.

In this regard, they questioned not only the top-down and bureaucratic management of resources and basic services for agricultural work, but also the lack of differentiated, motivational attention to younger producers. This undermines their perception of equitable treatment and, therefore, discourages them from remaining as productive forces, with other employment and economic options in general, outside of agriculture and the rural context, being more attractive.

Particularly in the criteria regarding Minag officials at the local level, they were accused not only of hindering cooperative work, but also of limiting the demands of the majority as productive forces from reaching the central government, with dissatisfaction or a perception of disadvantage.

They also criticized the high prices charged by the Ministry of Agriculture's Logistics Business Group for technological inputs for cooperative production, in the absence of other alternatives, or because they are economically unviable for individuals in the international market, which jeopardizes the success and sustainability of agricultural work.

Another criticism was directed at the actions of the state agricultural company, which was described as ineffective in its economic administrative functions. At the same time, cooperative members highlighted the material security for state producers as being much higher than that received by the CCS. Both factors were considered to generate a self-perception of disadvantage and lack of autonomy for cooperative agricultural work and, consequently, a loss of motivation for it, with an emphasis on the younger generations.

Several cooperative members agreed that their own boards of directors saw their decision-making autonomy affected and, therefore, the scope of producers' participation in important decisions for collective work and success, due to impositions or limitations by Minag officials in the territory. One aspect highlighted in this regard was the search for alternatives for purchasing inputs and resources outside the state-owned companies designated for this purpose.

Closely related to the above, perceptions were identified that it was precisely the lack of priority given to ensuring equitable material resources for the CCS that acted as external pressure on the presidents of the cooperative to prioritize those producers considered to have higher and more stable yields. This decision was valued as a catalyst for dissatisfaction in the community, perceptions of unfair treatment, and, consequently, demotivation toward work efficiency in a significant part of these productive forces.

Training was one of the opportunities considered to be at a disadvantage by the CCS. They considered the options for participating in projects coordinated by the provincial Scientific Complex institutions to be unfair, except for producers with a track record recognized by Minag and Anap in the territory. In this regard, young people were mentioned with emphasis as being affected by a lack of opportunities for access to technology, financing, and prosperity for their work, which would have come from the possibility of participation in such projects.

Other practices highlighted as unfavorable for the sociocultural preservation of agricultural work were the loss of promotion of this activity by Anap, Minag, and the Ministry of Education (Mined). In this case, the criteria of producers and experts highlighted the loss or significant decline, for example, of interest groups in which schoolchildren used to participate, as well as workshops with primary school students, etc.

The information obtained from leading producers and from the content of previous studies revealed that among the concepts and practices harmful to labor equity in CCS, there was growing questioning among producers themselves about the usefulness of their organization. This, in addition to denoting the self-perception of private actors in agricultural work above the ethics of collectivity, was considered an unfavorable element for the sustainability of agricultural work, compared to other sectors.

On the other hand, among the risks attributed to the sociodemographic characteristics of the groups associated with the CCS, those related to age were most prominent. However, the data on the minority presence of women as members (35 in the Nelson Fernández CCS, 29 in the René O. Reiné CCS, and 81 in the Camilo Cienfuegos CCS), contrasted with previous information on the tendency of women not to formally join associations, reaffirmed the detrimental nature of this behavior for equity in agricultural work, in terms of lower contribution and recognition as productive forces.

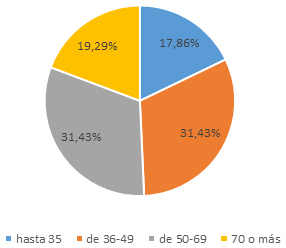

Specifically, in terms of age, at the time of this research, the 140 members of the Nelson Fernández CCS had a high average age of 56, with 6 of the 10 legal owners who were still alive over the age of 80, while only 25 were young (up to 35 years old).

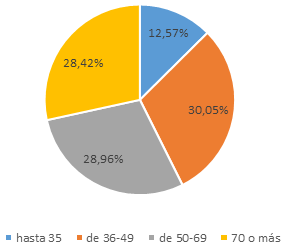

In a similar situation, according to official documentation, of the 183 members of the René O. Reiné CCS, the average age rose to 56, with a high number of 47 members over the age of 60 and only 23 young people.

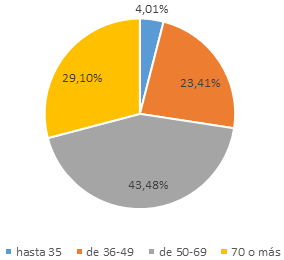

The situation of the Camilo Cienfuegos CCS was even more unfavorable in several respects. Among its 229 members, the average age exceeded 57, and more than 60 of those producers were already over 70, with a mere 12 young people.

Approaching to the three CCSs as a whole, there was a risk that, of the total of 552 members, the high average age exceeded 56, combined with the reduced presence of 60 young people aged up to 35, and the location of the highest percentages of members over the age of 50. These conditions were considered to have strong immediate and short-term implications for equity in agricultural work, associated, in the first instance, with disadvantages for the work and physical well-being of older adults. In turn, these risks were related to the lack of guarantees for generational replacement in agricultural activity.

The details of the data corresponding to age, as a manifestation of risks to equity in agricultural work, are shown in Graphs 1, 2, and 3 (one for each CCS explored). These show a distribution of the percentage of members in each age group, with those under 50 years of age being a large minority, especially in the Camilo Cienfuegos cooperative (the largest in terms of population and geographical area) and the Orestes O. Reiné cooperative.

Graph 1. CCS Nelson Fernández, percentage distribution of members by age group

Source: CCS characterization documents and doctoral thesis of the first author of the article

Graph 2. CCS René O. Reiné, percentage distribution by age range of members

Source: CCS characterization documents and doctoral thesis of the first author of the article

Graph 3. CCS Camilo Cienfuegos, percentage distribution by age range of members

Source: CCS characterization documents and doctoral thesis of the first author of the article

Finally, this research identified risks in the experts' approach to various structural and functional aspects of the dynamics of CCSs. The most significantly was that their analyses, as presented in the interviews, did not view workers who were not members of cooperatives but who played a key role on farms belonging to those organizations as social actors in this productive dynamic. By discursively reducing them to the mere status of hired laborers, the informality and precariousness of work in many of these cases becomes less visible from a scientific perspective.

Based on the information obtained, several manifestations could be synthesized, in terms of conceptions and practices, in the CCS and their related entities, where risks to agricultural labor equity were identified, as outlined below.

There was a perception that the only actors in agricultural work were the producers who owned the farms. The low visibility of agricultural workers and other employees in this study was considered unfavorable for addressing inequalities in their work, such as the disadvantage generated by the informality and precariousness of their employment relationship.

Related to the above, a risk was identified in the passive acceptance by hired agricultural workers of their informal employment status and the evasion of tax obligations related to their social security. This was assessed as unfavorable for equity, in terms of limited legal support for their security, but also in terms of few objective guarantees of well-being in the medium term.

Another risk to equity in agricultural work, specifically in relation to young producers running farms, was their limited representation in cooperatives with an aging membership. Added to this was the growing short-term commercial interest in these young people. The first element was seen as a limitation, above all, to equal opportunities between generations of members, who were involved in dynamics with social roles and relationships already dominated by those with more experience. The second was considered to create disadvantages for agricultural work in general, in terms of identification with this activity and, therefore, sustainability, compared to other economic sectors in the country.

Along with the low presence of young people among cooperative members, the advanced age of the majority was assessed as a high risk for equity in agricultural work within the CCS, as it implies objective conditions of vulnerability for long-standing producer-workers and an overload for those with less experience.

The reluctance of women to take on the role of formal members of cooperatives was identified as a risk, reflected in their unequal access to necessary resources and services provided by the boards of directors.

Risks were also identified in the criteria of CCS producers, who considered their cooperative work to be at a disadvantage compared to state-run forms of production, as well as in the lack of differentiated attention to younger producers and the loss of institutional practices to promote this activity by Minag, Anap, and Mined. These factors were identified as detrimental to motivation and job retention, compared to other sources of economic growth associated with less physical exertion and faster monetary gains in urban contexts.

The category of risks was practically not used in the theoretical underpinnings systematized for this research. However, several of these terms corresponded to the risks identified, in an exploratory manner in this research, for equity in agricultural work in the selected CCS.

This was evident in the argumentation of unfavorable implications of certain conceptions and practices in the CCS or their related entities for participation in equal conditions for the different cooperative actors in agricultural work, as well as between them and the productive forces of the state sector.

Assuming these unfavorable conditions and implications in the medium and long term as risks would make it easier to clearly identify priorities in emerging or strengthening issues, based on public policies aimed at the agricultural sector. This identification, in turn, reaffirms what has been proposed by social scholars of equity, referenced in the article, regarding the insufficiency of legal or formal norms in their favor, when in practice there are conceptions and behaviors contrary to what has been instituted, which demonstrate the need to focus on a more realistic notion of the particularities in territories and productive organizations, such as the CCS.

These results allow to summarize several final considerations. First, equity in agricultural work in Cuba, understood as equality of opportunity, rights, and basic starting conditions, access to basic resources and services, material and symbolic well-being proportional to results, and the leveling of initial objective disadvantages, is at risk due to the concepts and practices of the CCS and its related entities, which have unfavorable effects in terms of disadvantaged access to resources, basic services, and monetary income, as well as the participation and well-being of actors in different occupations and forms of productive management.

Key risks identified for agricultural labor equity in the CCS sector are: the perception of farm owners as the main actors in agricultural labor, low visibility of hired workers, informal hiring and social security tax evasion by mutual agreement between the parties, little awareness among women of the benefits of being CCS members, high average age of producers, low number of young people in this category, short-term commercial interest in these younger producers, the perception of obstacles attributed to the management of basic Minag procedures for work, dissatisfaction with the state's non-payment for production, and the lack of promotion and cultural preservation of agricultural activity.

The foreseeable effects of these and other elements considered risks to equity in agricultural work are: failure to recognize specific human development problems of hired agricultural workers, or guarantees for their long-term well-being; results that generate discontent and, therefore, demotivation among productive actors, due to disadvantageous or unstable procedures and assurances; loss of sources of income and other forms of spiritual empowerment of work for women, by not joining the CCS; few guarantees of the sustainability of agricultural activity as a means of economic sustenance, family life and, therefore, the material and spiritual reproduction of the nation, in the face of economic activities in urban contexts.

REFERENCES

Arias Guevara, M. de los Á., & Leyva Remón, A. (2019). Cuba: Transformación agraria, cooperación agrícola y dinámicas sociales. Ciências Sociais Unisinos, 55(1), 86-96. https://doi.org/10.4013/csu.2019.55.1.09

Beck, U. (2002). La sociedad del riesgo global (J. Alborés Rey, Trad.). Siglo XXI. https://www.felsemiotica.com/descargas/Beck-Ulrich-La-Sociedad-Del-Riesgo-Global-copia.pdf

Díaz Machado, N. (2024). Expresiones de cultura política que implican riesgos para los fines de la política agraria, estudio de casos de cooperativas en San José de las Lajas, provincia de Mayabeque [Doctorado en Ciencias Sociológicas, Universidad de La Habana]. https://accesoabierto.uh.cu/s/scriptorium/item/2195722

Díaz Machado, N., Moore Pedroso, M., & González Marrero, A. (2021). Condicionantes de la sostenibilidad del sector agrario asociadas a transformaciones sociopolíticas del ámbito cooperativo. Cooperativismo y Desarrollo, 9(3), 883-904. https://coodes.upr.edu.cu/index.php/coodes/article/view/465

Donéstevez Sánchez, G., & Muñoz González, R. (2017). Políticas y régimen agrario en la transición socialista en Cuba. Una mirada desde la economía crítica. En A. Leyva Remón & D. Echevarría León, Políticas públicas y procesos rurales en Cuba. Aproximaciones desde las Ciencias Sociales (pp. 37-38). Editorial de Ciencias Sociales / Ruth Casa Editorial. https://www.agter.org/bdf/es/corpus_chemin/fiche-chemin-826.html

Echevarría León, D. (2020). Desigualdades económicas e interseccionalidad: Análisis del contexto cubano 2008-2018. Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales / Publicaciones Acuario, Centro Félix Varela. https://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Cuba/flacso-cu/20201103111306/4-Desigualdades-economicas.pdf

Espina Prieto, M., & Echevarría León, D. (2020). El cuadro socioestructural emergente de la `actualización' en cuba: Retos a la equidad social. International Journal of Cuban Studies, 12, 29-52. https://doi.org/10.13169/intejcubastud.12.1.0029

García Álvarez, A. (2020). El sector agropecuario y el desarrollo económico: El caso cubano. Economía y Desarrollo, 164(2). https://revistas.uh.cu/econdesarrollo/article/view/1726

González Marrero, A., Díaz Machado, N., Brito Montero, A., Báez Fernández, D., & Sánchez Ortega, N. (2024). La cultura agraria en la Estrategia de Desarrollo Municipal de San José de las Lajas: Un análisis crítico. Gestión del Conocimiento y el Desarrollo Local, 11(3). https://revistas.unah.edu.cu/index.php/RGCDL/article/view/2043

Hidalgo López-Chávez, V. (2020). Desigualdades territoriales e interseccionalidad. Análisis del contexto cubano 2008-2018. Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales / Publicaciones Acuario, Centro Félix Varela. https://libreriacentros.clacso.org/publicacion.php?p=2350&cm=248

Izquierdo Quintana, O., & Martín Romero, J. L. (2022). La evolución del trabajo en Cuba: Una mirada histórica con lentes sociológicos. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/fescaribe/19208.pdf

Leyva Remón, A., & Echevarría León, D. (2017). Políticas públicas y procesos rurales en Cuba. Aproximaciones desde las Ciencias Sociales. Editorial de Ciencias Sociales / Ruth Casa Editorial. https://www.agter.org/bdf/es/corpus_chemin/fiche-chemin-826.html

López Belloso, M., Silvestre Cabrera, M., & García Muñoz, I. (2021). Igualdad de Género en instituciones de educación superior e investigación. Investigaciones Feministas, 12(2), 263-270. https://doi.org/10.5209/infe.76643

Luhmann, N. (1992). Sociología del riesgo. Universidad Iberoamericana / Universidad de Guadalajara.

Martín Romero, J. L. (2020). El trabajo en la actualización o la actualización del trabajo. Un proyecto indispensable. Novedades en Población, 16(32), 54-78. https://revistas.uh.cu/novpob/article/view/456

Muñoz Subía, K. B., & Pangol Lascano, A. M. (2021). Igualdad y no discriminación de la mujer en el ámbito laboral ecuatoriano. Universidad y Sociedad, 13(3), 222-232. https://rus.ucf.edu.cu/index.php/rus/article/view/2092

Nova González, A. (2022). Agricultura en Cuba. Entre retos y transformaciones. Editorial Caminos. https://www.libreriavirtual.cu/agricultura-en-cuba-entre-retos-y-transformaciones

Onei. (2022). Anuario Estadístico Provincial Mayabeque 2021. Oficina Nacional de Estadística e Información. https://onei.gob.cu/aep-mayabeque-2021

PCC. (2016). Actualización de los Lineamientos de la Política Económica y Social del Partido y la Revolución para el periodo 2016-2021. Partido Comunista de Cuba. https://www.granma.cu/file/pdf/gaceta/01Folleto.Lineamientos-4.pdf

Zabala Arguelles, M. del C., Fundora Nevot, G. E., & Echevarría León, D. (2022). Apuntes para la comprensión de desigualdades y equidad en el modelo de desarrollo socialista cubano. Estudios del Desarrollo Social: Cuba y América Latina, 10(3), 1. https://revistas.uh.cu/revflacso/article/view/7

Notes

1 By assigning CCS a lower degree of ownership socialization, political priority was given to strengthening the other two types of existing cooperatives. These were the Agricultural Production Cooperatives (CPA), with land as the collective property of the organization, and the Basic Cooperative Production Units (UBPC), where members were usufructuaries of plots legally belonging to state agricultural enterprises. An example of this prioritization was that, within the framework of the thesis of the First Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba and the propaganda of the National Association of Small Farmers, until the late 1980s, CCSs were seen as a transition to CPAs, which were considered a superior form of production due to their extensive formal collectivization.

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' contribution

Nayibis Díaz Machado conceived the study.

Nayibis Díaz Machado and Alfredo González Marrero prepared the draft of the study.

All authors were involved in the study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. They also participated in the critical review of the article and in drafting the final version for submission to the journal.