0000-0002-3582-0514

0000-0002-3582-0514  bettysl1997@gmail.com

bettysl1997@gmail.comFrancisco Fidel Feria Velázquez1

0000-0001-7705-4849

0000-0001-7705-4849  frferia581231@gmail.com

frferia581231@gmail.comFélix Díaz Pompa1

0000-0002-2666-1849

0000-0002-2666-1849  felixdp1978@gmail.com

felixdp1978@gmail.com

Cooperativismo y Desarrollo, September-December 2023; 11(3), e575

Translated from the original in Spanish

Original article

Creative Placemaking: an alternative in post-Covid times

Placemaking Creativo: alternativa en tiempos pos-Covid

Placemaking Criativo: alternativa em tempos pós-Covid

Beatriz Serrano Leyva1  0000-0002-3582-0514

0000-0002-3582-0514  bettysl1997@gmail.com

bettysl1997@gmail.com

Francisco Fidel Feria Velázquez1  0000-0001-7705-4849

0000-0001-7705-4849  frferia581231@gmail.com

frferia581231@gmail.com

Félix Díaz Pompa1  0000-0002-2666-1849

0000-0002-2666-1849  felixdp1978@gmail.com

felixdp1978@gmail.com

1 University of Holguín "Oscar Lucero Moya". Holguín, Cuba.

Received: 6/12/2022

Accepted: 16/10/2023

ABSTRACT

The post-Covid scenario is an opportunity to rethink the cultural tourism model that already showed negative symptoms such as overtourism, lack of economic resources and lack of authenticity. Creative placemaking in the context of creative tourism has the potential to mitigate these effects. The objective of the research was to identify the potentialities of creative placemaking in Holguin destination for the development of creative tourism. The descriptors creative tourism were searched in Scopus and the position of creative placemaking in this theoretical structure was identified by means of SciMAT software. A content analysis of the articles on creative placemaking was carried out to identify its dimensions. A thesaurus was developed to replace keywords by the label of each dimension and analyze the density by keyword co-occurrence in VOSviewer. The key factors of each dimension were analyzed using keyword co-occurrence maps. The factors were discussed with specialists in the field to identify the potentialities of the Holguin destination. Creative placemaking is a transversal theme, important, but little addressed. The dimensions that emerged as dimensions were the principles proposed by Greg Richards: resources, meaning and creativity. Holguín has potential for the development of creative placemaking in the city and rural areas. The mapping of creative enterprises and their conjunction in a digital platform for the co-creation of experiences and commercialization is necessary. The article provides a first approach to the subject to be considered for the conception of a new model of cultural tourism management oriented to creative tourism.

Keywords: Holguín tourist destination; creative placemaking; post-Covid times; creative tourism.

RESUMEN

El escenario pos-Covid es una oportunidad para repensar el modelo de turismo cultural que ya mostraba síntomas negativos como el sobreturismo, la carencia de recursos económicos y la falta de autenticidad. El placemaking creativo en el contexto del turismo creativo posee potencialidades para mitigar estos efectos. El objetivo de la investigación fue identificar las potencialidades de placemaking creativos en el destino Holguín para el desarrollo del turismo creativo. Se buscaron los descriptores creative tourism en Scopus y se identificó la posición del placemaking creativo en esta estructura teórica mediante el software SciMAT. Se realizó un análisis de contenido de los artículos sobre placemaking creativo para identificar sus dimensiones. Se elaboró un tesauro para remplazar las palabras clave por la etiqueta de cada dimensión y analizar la densidad mediante la co-ocurrencia de palabras clave en VOSviewer. Se analizaron los factores clave de cada dimensión mediante mapas de co-ocurrencia de palabras clave. Los factores fueron discutidos con especialistas del tema para identificar las potencialidades del destino Holguín. El placemaking creativo es un tema transversal, importante, pero poco abordado. Resultaron como dimensiones los principios propuestos por Greg Richards: recursos, significado y creatividad. Holguín posee potencialidades para el desarrollo de placemaking creativos en la ciudad y espacios rurales. Es necesario el mapeo de emprendimientos creativos y su conjunción en una plataforma digital para la co-creación de experiencias y comercialización. El artículo brinda un primer acercamiento al tema a considerar para la concepción de un nuevo modelo de gestión del turismo cultural orientado al turismo creativo.

Palabras clave: destino turístico Holguín; placemaking creativos; tiempos pos-Covid; turismo creativo.

RESUMO

O cenário pós-Covid é uma oportunidade para repensar o modelo de turismo cultural que já apresentava sintomas negativos, como o excesso de turismo, a falta de recursos econômicos e a falta de autenticidade. O placemaking criativo no contexto do turismo criativo tem o potencial de mitigar esses efeitos. O objetivo da pesquisa foi identificar o potencial do placemaking criativo no destino Holguín para o desenvolvimento do turismo criativo. Os descritores turismo criativo foram pesquisados no Scopus e a posição do placemaking criativo nessa estrutura teórica foi identificada usando o software SciMAT. Foi realizada uma análise de conteúdo dos artigos sobre placemaking criativo para identificar suas dimensões. Um tesauro foi desenvolvido para substituir as palavras-chave pelo rótulo de cada dimensão e para analisar a densidade por co-ocorrência de palavras-chave no VOSviewer. Os principais fatores de cada dimensão foram analisados por meio de mapas de co-ocorrência de palavras-chave. Os fatores foram discutidos com especialistas da área para identificar o potencial do destino Holguín. A criação de locais criativos é um tema transversal, importante, mas pouco abordado. As dimensões que surgiram como dimensões foram os princípios propostos por Greg Richards: recursos, significado e criatividade. Holguín tem potencial para o desenvolvimento de placemaking criativo na cidade e nas áreas rurais. É necessário o mapeamento de empreendimentos criativos e sua combinação em uma plataforma digital para a co-criação de experiências e comercialização. O artigo fornece uma primeira abordagem do assunto a ser considerado para a concepção de um novo modelo de gestão do turismo cultural orientado para o turismo criativo.

Palavras-chave: destino turístico de Holguín; placemaking criativo; tempos pós-Covid; turismo criativo.

INTRODUCTION

Tourism is facing an unprecedented situation due to the impacts of the crisis caused by Covid-19. This situation offers a unique opportunity to evaluate current tourism models that have shown limitations for effective management. Before the pandemic hit the world, several debates had already been generated regarding the negative symptoms of cultural tourism, such as: overtourism, lack of funds for the rehabilitation of cultural resources and lack of authenticity in the design of tourism experiences.

"This crisis invites us to design tourism models where natural and cultural assets are valued and protected, where the way of life of local communities is not disrupted and their intangible cultural heritage is safeguarded, and where creativity is encouraged to flourish. More resilient models of tourism are required that are in harmony with the environment, that protect livelihoods and from which local communities can benefit" (Unesco, 2020, p. 2).

In this context, creative tourism appears as an alternative. It is a young tourism modality, but one that is gaining more and more followers every day based on its potentialities, including the possibility of mitigating mass tourism (Duxbury & Richards, 2019) through effective management. Its basic resource is creativity, which gives it important competitive advantages by adding value to the experience through product innovation.

It is worth noting that creative tourism has its roots in cultural tourism. The conception of cultural tourism has taken on a dynamic and transforming character over the years, based on the premise of meeting the needs of the demand according to different historical contexts. Richards (2018) and Sacco (2011) propose the existence of several stages; the first: cultural tourism 1.0, which takes place as a result of the Grand Tour, a phenomenon that occurs in the sixteenth century and consisted of trips by young people from the English nobility and middle class across the continent to complement knowledge and experiences. At this stage, cultural tourism was limited to a small elite.

In contrast, cultural tourism 2.0 is oriented towards massification, based on the development of cultural resources and attractions. In fact, its contribution to the European economy in the post-World War II period is recognized. Consequently, by the early 1990s cultural tourism development was well established in many destinations (Richards, 2018).

The implementation of cultural tourism 2.0 proved to be a valuable contribution to economic development. Cities compete with each other to attract a large number of cultural tourists and maximize their spending on the development of their own culture. In this context, the creation of experiences plays a determining role and, sometimes, there is a lack of authenticity in their conception.

On the other hand, there is also a deterioration of the heritage and of the tourists' own experience in large cities as a consequence of overcrowding, including: the rejection of the local population due to perceived nuisances such as noise and competition for space. The emergence of anti-tourism movements and even acts of vandalism are becoming increasingly frequent (Frey & Briviba, 2021) as a response to this situation and the rapid growth of tourist infrastructures.

In addition, with the economic crisis, the synergy between culture and tourism has been questioned due to the existence of limited funds for investment, sometimes caused by the fact that the cultural sector in many places has expressed the idea that culture should have affordable prices for the population because it is a good for the community (Richards, 2001).

With the withdrawal of public funds for culture, a new approach has been fostered, cultural tourism 3.0, which no longer stimulates massification and is oriented towards culture as a source of value, through the personalization of co-created experiences, based on new technologies. Tourists play an active role, seeking to develop their creative potential, and cities take care to provide a satisfactory environment for this type of tourist (Sacco, 2011).

The growing recognition of the importance of creativity in tourism has led to the existence of creative sub-areas (Richards & Raymond, 2000) that break with the traditional models of cultural tourism. The objective is to offer unique experiences that differentiate destinations, leaving aside traditional production approaches aimed at mass tourism. These experiences are based on the "experience economy", which seeks to satisfy and retain consumers by providing them with only the products they have requested.

Therefore, the aim is to involve tourists in the design, production and consumption of the experience, a process known as co-creation. This concept takes on a relevant value in tourism, based on its differentiating characteristics such as the intangibility of the service. Taking into account the cultural experience that the client wants to live and building it according to his or her expectations provides greater guarantees of satisfaction. As a result, tangible heritage is no longer an indispensable condition for cultural tourism, but has expanded towards a more comprehensive vision of creative tourism, which focuses on the consumer experience.

Creative tourism has its origins in the 1990s, linked to the EUROTEX project, which sought to preserve artisanal production by marketing it to tourists. To do so, it was necessary to show the value of these productions to tourists in comparison with serial productions (Richards, 2009). Its development made it possible to verify that many tourists showed interest in seeing how these productions were made, and even in learning these techniques. Therefore, the genesis of creative tourism is cultural, based on the integration of tourism with the creative industries.

The term creative tourism was coined by professors Greg Richards and Crispin Raymond in 2000, to refer to the tourism modality that enables consumers to develop their creative potential through experiences based on active participation in host communities (Richards & Raymond, 2000). This definition corresponds to creative tourism 1.0 seen on a local scale. In its second phase, creative tourism presents a broader scope, uses the Internet as a mediator of an offer marked by authentic experiences, characterized by participatory learning and the necessary connection with the culture and hosts of the place (Duxbury & Richards, 2019, pp. 1-14).

The incorporation of activities and the link with creative industries in recent decades mark the arrival of creative tourism 3.0 (Duxbury & Richards, 2019) characterized by creative activities based on knowledge and co-created between producers and consumers through the use of technology to generate experiences based on intangible heritage. Creative tourism differs from traditional cultural tourism by being oriented to the future and not to the past, it seeks innovation and its structure is not based on products, but on platforms and content. It focuses on the co-creation of experiences and not on interpretation (OECD, 2014).

Creative tourism experiences are created from unique local cultural assets, encouraging the active participation of the tourist and a teaching role on the part of the host. These activities are designed to stimulate the human senses, enhance creativity and induce innovation. Therefore, managers of this type of tourism must be able to creatively communicate the distinctive identity of the place and promote constant improvement in the experience.

Creative tourism is not a magic solution to reverse the development of mass cultural tourism, but it offers alternatives focused on a more personalized management that benefits the community. Within the international framework, its development is increasingly being promoted. Unesco itself, with the founding of the Creative Cities Network in 2004, identifies creativity as a strategic factor. In 2010, the Creative Tourism Network was founded to promote creative destinations around the world. This organization awards the Creative Friendly Destination seal and the Creative Tourism Award to companies, projects and destinations that are committed to creative tourism.

The value of creative tourism is magnified in the current context, where the Covid-19 pandemic in the tourism framework has meant more than 60 million fewer tourists worldwide and losses of more than US $80 billion; cultural tourism accounts for almost 40% of global tourism revenues, so the impacts for the cultural and creative tourism industry have been significant. By June 2020, 95% of museums had closed and 13% with no hope of reopening; 9 out of 10 countries had closed their World Heritage sites, while several intangible cultural practices were disrupted. Host communities and workers in the sector were also hit. Unprecedented impacts on the cultural tourism sector (Unesco, 2020).

With the effects of Covid-19, the international tourism community has focused on possible alternatives, and there are several proposals with a markedly innovative character. However, it should be taken into account that the consumer will never be the same again, tourism will never be the same again, and it is even worth reflecting on whether it would actually be positive to return to the normality to which many aspire (Richards, 2020b). Richards (2020b) provides an excellent reflection when he refers to the point at which cultural tourism was at the stage prior to the arrival of Covid-19, the effects of overcrowding and the lack of authenticity in the offer. The post-Covid context must be assumed then as a challenge to innovate management models towards the development of creativity.

Creative tourism develops the creative potential of tourists, promotes their learning and greater satisfaction through the co-creation of experiences. It guarantees a high level of participation by the local community, which helps to improve their quality of life and create stronger ties with the destination (Richards & Raymond, 2000). Creative tourism is a more sustainable way of doing tourism.

As a result, several destinations such as Portugal, Brazil, Thailand, Spain, among others, have opted for creative tourism. Its development has been very successful in large and small cities, as well as in rural areas. Thus, the creative tourism modality can be developed at different territorial scales. In this endeavor, the concept of creative placemaking plays a fundamental role in creative tourism.

Therefore, creative tourism can contribute to mitigating the effects of the crisis by achieving longer stays by customers through the diversity of types of activities it offers. Destinations should work based on the management of creative spaces, actions that summarize creative placemaking.

The concept of placemaking dates back to the 1970s and there is no consensus on its definition (Zuma & Rooijackers, 2020). Its meaning (place design, planning and management) is framed in an interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary dynamic social context, and is influenced by Geography, Economics, Public Policy, Political Science, Sociology, Psychology, Law, Architecture, Building Sciences, Technology and Marketing (Sofield et al., 2017). Hence, it is associated with architects, geographers, urban planners and designers (Gato et al., 2022).

Although the concept of placemaking does not originate in tourism, in the framework of creative tourism it focuses on the planning, design and management of spaces that support the development of creativity. Creative placemaking can contribute to connecting people, places and resources (Gato et al., 2022), as well as generating benefits for the community. Its development is also important for many cities that have tried to position themselves in this new economic landscape as "creative cities" or those that have potential for the development of creative tourism.

It is not a concept born with tourism, however, creative tourism practices are inclined to change the approach in the creation of places, where it is not restricted to a top-down approach (Sofield et al., 2017), but involves all stakeholders. Creative placemaking aims to maximize the generation of value and achieve a greater role of the local community, therefore, it is an alternative that should be valued in those spaces with the potential for the development of creative tourism.

Placemaking in creative tourism fosters community progress through cultural artistic expressions. Plans are designed based on the demands of the villagers to improve their environment and quality of life (Schroeder & Coello Torres, 2019). To achieve this, authorities seek to establish strong links between residents and cities or regions, which influences consumer perception. The focus of the brand is changing, giving greater importance to local residents and businesses, which strengthens the image of the destination by showing a standardized identity.

Evans (2015) describes creative areas as those that tend to be most successful in attracting tourists when they have not been planned or developed from the top down, but rather when they have occurred organically. Policymakers need to detect where such areas can emerge and thus support and facilitate their development.

In this context, the tourist destination Holguín, which is located in the northeastern part of Cuba, has excellent natural and historical-cultural attractions that distinguish it and propitiate the development of the tourist activity. The main modality that it develops is the tourism of Sun and Beach, motivation of more than 70 % of the visits of the international tourism. The destination is in the consolidation stage of its life cycle, so there is a need to rejuvenate the offer. The presence of travel agencies for promotion, national and international events throughout the year, cultural institutions, as well as a rich tangible and intangible heritage, provide opportunities for the design and planning of creative places in the destination. The objective of the study is to identify the potential of creative placemaking in Holguin destination for the development of creative tourism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

To identify the place of creative placemaking within the theoretical structure on creative tourism, an analysis was carried out with the help of SciMAT software, which identifies the level of development of the topics through the co-citation of keywords. For this purpose, a search for the thematic descriptor "creative tourism" was carried out in titles, abstracts and keywords of articles indexed in the Scopus database. The time frame was limited to May 23, 2022, the date on which the search was conducted.

The SciMAT software, by means of a co-word network, obtains a group of keywords and connections which are called themes. These themes are placed in a strategic diagram according to density and centrality values. The strategic diagram, composed of two two-dimensional spaces, allows identifying that the themes in the upper-right quadrant (high centrality and density) are driving themes and are related to other themes. In the upper-left quadrant (very well-developed internal links) are the specialized and peripheral themes. In the lower-right quadrant, there are the transversal and generic topics, basic for the knowledge of the scientific field. In the lower-left quadrant are the emerging or disappearing topics.

Then, the articles dealing with creative placemaking were identified in order to carry out a content analysis of them, which allowed to determine the basic dimensions for their study. The transversality of the subject was considered, identified by means of SciMAT software, and the variables corresponding to each dimension were identified by analyzing the keywords contained in the scientific production on creative tourism.

A thesaurus was developed to replace the keyword label with the name of the corresponding dimension. A density analysis of each dimension was performed in the VOSviewer software. The density view is useful to obtain an overview of the most important areas of a map. Keyword co-occurrence maps per dimension were then produced in VOSviewer for interpretation. The elaboration of the co-occurrence maps takes into account the similarity or strength of association of the keywords, where the closer the keywords are on the map, the greater the association of the descriptors is inferred.

Based on the resulting elements, the key factors that served as a guide for the analysis of the potential of Holguin as a tourist destination for creative tourism were drawn up through an exchange with specialists in the subject, complemented by a review of the literature.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

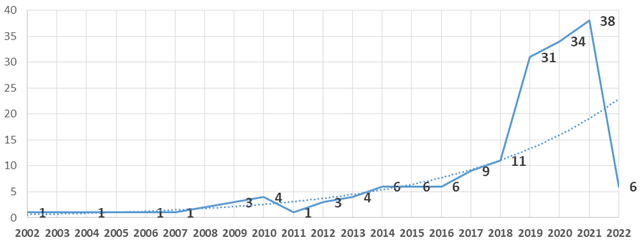

The Scopus search yielded a total of 166 articles. In the graph (Fig. 1) the trend line shows the exponential growth of publications. Despite the youth of the subject, there is evidence of a sustained and growing interest of authors in creative tourism, especially in the last two years, where the importance of creativity in tourism has been recognized by the World Tourism Organization as a challenge within the necessary synergy between culture and tourism to achieve authentic and innovative experiences.

Figure 1. Scientific production on creative tourism in Scopus

Source: Own elaboration

According to the strategic diagram (Fig. 2), elaborated by processing the resulting database in the SciMAT software, creative placemaking is an important topic within creative tourism, but it is not very developed. It is a transversal and generic topic; therefore, it is basic to the knowledge about the scientific field analyzed.

Figure 2. Strategic diagram on creative tourism

Source: Own elaboration

In the search for papers that addressed creative placemaking as a central theme, only the contributions discussed below were found. Sofield et al. (2017) study the role of community and organic folk expressions of their identity in placemaking, contextualized to the development of public spaces in Tasmania, Australia. The authors posit that placemaking is a social construction and when the community has direct participation and control in this process, the role of tourism is limited to the commercialization of the place in the creative tourism mode. The Tasmanian experience demonstrates the importance of image in attracting consumers and the necessary role of the community in achieving sustainable urban tourism.

For their part, authors Zuma and Rooijackers (2020) illustrate the potential of urban culture for creative placemaking through two case studies: The Notorious IBE (International Breaking Event) and EMOVES (urban culture festival), which attract thousands of participants. They refer to the youth culture of breakdancing, apropos of its incorporation as an Olympic discipline in the Paris 2024 games, as an opportunity for tourism.

Nieuwland and Lavaga (2020) conducted a study of the city of Rotterdam in the Netherlands, considered Capital of European Culture, which after a process of deindustrialization seeks to position itself as a creative city through the development of arts and culture. The authors analyze the role of creative entrepreneurs in the design and creation of creative spaces for the development of sustainable urban tourism. It is argued that despite the importance given to creative entrepreneurs from a theoretical point of view, in practice they are often not taken into account in the design and creation of creative places.

Gato et al. (2022) analyze as case studies the development of placemaking in peripheral areas of Portugal. The authors argue that peripheral areas are characterized by low population densities, marked aging and population loss, as well as the existence of a less competitive rural and economic structure. The article discusses how creative placemaking can contribute to raising the quality of life and self-esteem of the local population. The study highlights the importance of the CREATOUR project in framing and strengthening creative tourism experiences. For the analysis, the authors use as a reference the principles proposed by Richards (2020a): resources, meaning and creativity that guide the essence of creative placemaking. The importance of the articulation between top-down and bottom-up placemaking strategies to achieve solid and sustainable creative tourism experiences is evidenced.

The contribution of Richards (2020a), one of the pioneers of the creative tourism concept together with Professor Crispin Raymond, was also analyzed. Greg Richards is one of the most prolix and cited authors in the literature on creative tourism. On this occasion, the author presents case studies on creative placemaking at different scales such as rural areas, small cities, large cities and creative regions. The importance of creativity as a strategy for the development of placemaking is shown. It also contextualizes placemaking in the framework of tourism and provides a theoretical basis for the elements of creative placemaking comprising resources, meaning and creativity.

Richards (2020a) ascribes to the positions of different authors, considering resources as endogenous tangible and intangible elements, as well as external assets that can be accessed through collaboration and networking and that are developed through the development of capabilities. As for meaning, it is generated through the combination of people, events and locations (Harrison & Tatar, 2008). Creativity is considered as a "ubiquitous, collective and relational process" (Montuori, 2011); therefore, creative development can be considered as a system of co-creation, where tourists as well as residents and tourism managers are involved.

The review of previous studies on creative placemaking evidences the importance of the principles: resources, meaning and creativity, contributed by Richards (2020a) and employed by Sofield et al. (2017). Similarly, the rest of the authors consulted work these elements, which evidences the importance of these principles as a guide for its development. It is also considered, as indicated by the SciMAT output, that this is a cross-cutting theme and that the consultation of other literatures on creative tourism allows a better understanding of the elements resources, meanings and creativity (considered dimensions of creative placemaking hereinafter) to be applied in placemaking.

Accordingly, a keyword analysis of all the scientific production available in Scopus on creative tourism was carried out. A total of 783 keywords was obtained, which were replaced by the name of the corresponding dimension for the density analysis (Fig. 3). The map shows the general structure of the topic with respect to dimensions, resources, meaning and creativity. Creativity is shown as the densest area, reflected by 108 co-occurrences, representing the strength of association of the items. In second place, resources (99 co-occurrences) and finally the meaning dimension with (47 co-occurrences).

Figure 3. Density map of creative placemaking dimensions

Source: Own elaboration

The analysis of the variables of each dimension was carried out individually to ensure greater clarity. The main results are summarized below (Tables 1, 2 and 3).

Table 1. Dimension: Resources

Keyword co-occurrence map |

|

Notes on map interpretation |

|

Key factors |

|

Source: Own elaboration

Table 2. Dimension: Meaning

Keyword co-occurrence map |

|

Notes on map interpretation |

|

Key factors |

These factors include authenticity, traditions, beliefs and identity as necessary elements to give meaning to the resources. |

Source: Own elaboration

Table 3. Dimension: Creativity

Keyword co-occurrence map |

|

Notes on map interpretation |

|

Key factors |

|

Source: Own elaboration

The tourist destination Holguín has numerous potentialities for the development of creative placemaking. It has more than 200 places of tourist interest and more than 50 cultural resources, which due to their location would allow the development of creative tourism both in the city and in rural areas. With regard to the city as a historic center, it should be noted that there is a strong cultural movement, although it is not fully exploited for tourism.

Cultural events are Holguín's strong point and are held throughout the year. In February, the Centro Promotor del Humor organizes the Festival de Humor para Jóvenes Satiricón, while the Teatro Guiñol de Holguín, Alas Buenas and Trébol Teatro participate in the Festival de Teatro Joven. In April, the International Film Festival is held in Gibara and in March the Book Fair and Las Romerías de Mayo are held. In September, the North Atlantic Dance Contest and the Vladimir Malakhov Grand Prix are held. In October, the Ibero-American House organizes the Ibero-American Culture Festival and in June, the Symphonic Orchestra offers a Concert Day for music lovers.

Having events already in place is a competitive advantage for the development of creative placemaking. Cultural and creative events involve different stakeholders and can encompass different experiences to meet the different needs of consumers There are countless activities and spaces that can be developed. The authors limit themselves to refer to a few examples.

As part of the Ibero-American Festival, the Ibero-American Crafts Fair takes place, a meeting for artisans from the eastern provinces of Cuba, as well as from other countries in the region. It promotes the exchange between painters, carvers, artisans and designers of the world. The event offers craft and plastic arts expo-sales, demonstrations of artisan work, fashion shows, launches of new products and cultural and recreational activities that attract tourists every year. This event can be an opportunity for the launching of creative products associated with other spaces (creative placemaking).

The Plaza de la Marqueta, an establishment linked to the culture and history of the people of Holguín, created in the 19th century and which recovered its commercial function in 2017 for the sale of handicrafts, is an excellent space for creative activities. Customers are not only interested in buying the products but in seeing and learning this art (Richards, 2009), if demonstrations of their elaboration were held there, as well as in the artisans' workshops, it can be gained in that tourists value their work more, which can contribute to raise the self-esteem of these creators. Crafts constitute an excellent link between culture, human creativity and the material world (OECD, 2014). Holguin's handicrafts are distinguished by a marked practical function, therefore, tourists' learning in this type of activity can offer them useful experiences. In addition, the human capital possesses experience and skills; Miriela Bermúdez Salazar, winner of the 2008 Master Craftsmanship Award, uses natural fibers to make Cuban dolls, unique in style and expression, can be mentioned. Juan Tomás Isla, winner of the UNESCO Excellence Award, is an outstanding creator who uses guaniquiqui fiber to weave ornamental and utilitarian objects.

In this framework, the 2019 Book-Art Collection was recently awarded for employing traditional techniques of elaboration, using natural materials and employing 18th century machines, by the team Taller de Impresiones Papiros (Ávila Pérez, 2019), a space that can offer a truly authentic experience to tourists, as well as the Engraving Workshop, where the client can have a participatory role and make his own engraving after some demonstrations.

The resources to be listed are many, parks that keep the historical memory of the people of Holguín, such as the parks Calixto García, Julio Grave de Peralta, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, José Martí and Rubén Bravo, are spaces that facilitate the realization of artistic activities such as the parades of living statues that provoke so much attention from the admirers.

Among the museums are the Carlos de la Torre Museum of Natural Sciences, La Periquera, La Casa Natal de Calixto García, where history still lives, however, activities such as theatrical representations of historical events or the inclusion of virtual reality technologies can provide a more authentic experience.

The possibility of bringing creative tourism to rural areas through novel experiences such as the planting and harvesting of coffee and traditional Cuban laundry cannot go unmentioned. These are native experiences that can be offered to clients. Creative tourism in rural areas contributes to local development and enhances the value of existing resources. There are several spaces in the destination that would allow its development.

The meaning of these resources lies in being authentic, in fostering pride in preserving the identity of the people of Holguín, in respecting beliefs and traditions. To show an image and brand of our own.

Finally, reference is made to two key aspects, the first is the use of technology. As can be seen, the destination has many resources that can be used in creative tourism experiences and that can make Holguín as a destination a creative space. The first steps can be oriented to the creation of a platform for the co-creation of experiences where creative tourism offers can be included according to the artistic manifestation to which it is directed. Secondly, it should be noted that in terms of governance, there are many facilities available based on current national policies that seek local development. As well as the post-Covid strategy that calls for the innovation of tourism products linked to other sectors such as culture.

This article constitutes an initial approach to creative placemaking in the Holguin destination. It is being working on a new model of cultural tourism focused on creative tourism, where the bases of that necessary synergy between culture, tourism, private sector and state sector in the design, planning and management of creative places are laid. Therefore, the implications of the research lie in a guide for the mapping of the destination's creative enterprises in order to give them meaning and provide creativity for their future management in accordance with the resulting new model.

REFERENCES

Ávila Pérez, J. M. (2019). Clausuran Iberoarte-2019 con entregas de premios en Holguín. Boletín del Fondo Cubano de Bienes Culturales. http://www.fcbc.cu/uploads/71230936.pdf

Duxbury, N., & Richards, G. (2019). A Research Agenda for Creative Tourism. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788110723

Evans, G. (2015). Rethinking Place Branding and Place Making Through Creative and Cultural Quarters. En M. Kavaratzis, G. Warnaby, & G. J. Ashworth (Eds.), Rethinking Place Branding: Comprehensive Brand Development for Cities and Regions (pp. 135-158). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12424-7_10

Frey, B. S., & Briviba, A. (2021). Revived Originals-A proposal to deal with cultural overtourism. Tourism Economics, 27(6), 1221-1236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816620945407

Gato, M. A., Costa, P., Cruz, A. R., & Perestrelo, M. (2022). Creative Tourism as Boosting Tool for Placemaking Strategies in Peripheral Areas: Insights From Portugal. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 46(8), 1500-1518. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348020934045

Harrison, S., & Tatar, D. (2008). Places: People, Events, Loci - the Relation of Semantic Frames in the Construction of Place. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 17(2), 97-133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-007-9073-0

Montuori, A. (2011). Beyond postnormal times: The future of creativity and the creativity of the future. Futures, 43(2), 221-227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2010.10.013

Nieuwland, S., & Lavanga, M. (2020). The consequences of being 'the Capital of Cool'. Creative entrepreneurs and the sustainable development of creative tourism in the urban context of Rotterdam. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(6), 926-943. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1841780

OECD. (2014). Tourism and the Creative Economy. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/industry-and-services/tourism-and-the-creative-economy_9789264207875-en

Richards, G. (2001). Cultural attractions and European tourism. CABI Publishing. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/book/10.1079/9780851994406.0000

Richards, G. (2009). Creative tourism and local development. En R. Wurzburger, S. Prat, & A. Pattakos (Eds.), Creative Tourism: A global conversation. (pp. 78-90). Sunstone Press.

Richards, G. (2018). Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 36, 12-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.03.005

Richards, G. (2020a). Designing creative places: The role of creative tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 85, 102922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102922

Richards, G. (2020b). The role of creativity in challenging times. 4th Bali International Tourism Conference, Bali.

Richards, G., & Raymond, C. (2000). Creative Tourism. ATLAS News, 23, 16-20. https://research.tilburguniversity.edu/en/publications/creative-tourism

Sacco, P. L. (2011). Culture 3.0: A new perspective for the EU 2014-2020 structural funds programming. OMC Working Group on Cultural and Creative Industries. https://www.interarts.net/descargas/interarts2577.pdf

Schroeder, S., & Coello Torres, C. (2019). Placemaking-Transformación de un lugar en el asentamiento humano Santa Julia, Piura, Perú. Hábitat Sustentable, 9(1), 6-19. https://doi.org/10.22320/07190700.2019.09.01.01

Sofield, T., Guia, J., & Specht, J. (2017). Organic 'folkloric' community driven place-making and tourism. Tourism Management, 61, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.01.002

Unesco. (2020). Cultura & Covid-19. Impacto & Respuesta. Boletín Semanal. https://es.unesco.org/sites/default/files/issue_12_es.1_culture_covid-19_tracker.pdf

Zuma, B., & Rooijackers, M. (2020). Uncovering the potential of urban culture for creative placemaking. Journal of Tourism Futures, 6(3), 233-237. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-10-2019-0112

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' contribution

Beatriz Serrano Leyva, Francisco Fidel Feria Velázquez and Félix Díaz Pompa designed the study, analyzed the data and prepared the draft. They participated in the analysis and interpretation of the information.

Beatriz Serrano Leyva and Francisco Fidel Feria Velázquez participated in the search for scientific information in Scopus and its processing by means of bibliometric software.

All the authors reviewed the writing of the manuscript and approve the version finally submitted.