https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7341-3832

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7341-3832 acobian@cajasmg.com

acobian@cajasmg.com

Cooperativismo y Desarrollo, September-December 2021; 9(3), 831-855

Translated from the original in Spanish

Cooperative Social Balance indicators for the Mexican savings and loan sector

Indicadores del Balance Social Cooperativo para el sector de ahorro y préstamo mexicano

Indicadores do Balanço Social Cooperativo para o setor de poupança e empréstimo mexicano

Áaron Cobián Puebla1; Jesús Juan Rosales Adame2; Ana del Carmen Fernandez Andrés3

1 Caja SMG y Universidad de Guadalajara. México.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7341-3832

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7341-3832

acobian@cajasmg.com

acobian@cajasmg.com

2 Universidad de Guadalajara. Departamento de Ecología y Recursos Naturales. México.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8694-7574

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8694-7574

jesusr@cucsur.udg.mx

jesusr@cucsur.udg.mx

3 Universidad de Camagüey. Facultad de Ciencias Económicas. Camagüey, Cuba.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5295-1543

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5295-1543

ana.fernandez@reduc.edu.cu

ana.fernandez@reduc.edu.cu

Received: 17/07/2021

Accepted: 24/10/2021

ABSTRACT

Both in practice and in academia, the contradiction between the social function performed by the Mexican savings and loan cooperative sector as a participant in the country's social economy and the almost non-existent practice of presenting non-financial information to its stakeholders is recognized. In this context, the objective of this study was to design a system of indicators for the preparation of the Social Balance Sheet in this sector of the Mexican social economy. The research carried out corresponded to a non-experimental mixed approach, where the Prisma methodology was applied with the content analysis technique, together with expert methods, the questionnaire technique and descriptive statistics. The main result achieved was the design of 91 indicators contextualized to the sector under study, which endorsed the need for a sectoral approach in its design to enable comparability and the implementation of common strategies for savings and loan cooperatives in Mexico, simultaneously with a classification of the proposed indicators into mandatory, complementary and optional in order to contribute to the achievement of the necessary flexibility of the proposal made.

Keywords: social balance sheet; indicators; savings and loan cooperative sector; sectoral

RESUMEN

Tanto en la praxis como en la academia, se reconoce la contradicción existente entre la función social que realiza el sector cooperativo de ahorro y préstamo mexicano como partícipe de la economía social del país y la práctica casi nula de exponer información no financiera a sus grupos de interés. En este contexto, el estudio que se presenta tuvo como objetivo diseñar un sistema de indicadores para la elaboración del Balance Social en este sector de la economía social mexicana. La investigación realizada correspondió a una no experimental de enfoque mixto, donde se aplicó la metodología Prisma con la técnica de análisis de contenido, conjuntamente con métodos de expertos, la técnica de cuestionario y la estadística descriptiva. El principal resultado alcanzado fue el diseño de 91 indicadores contextualizados al sector objeto de estudio, donde se refrendó la necesidad de un enfoque sectorial en su diseño que posibilitara la comparabilidad y la implementación de estrategias comunes para las cooperativas de ahorro y préstamo en México, simultáneamente con una clasificación de los indicadores propuestos en obligatorios, complementarios y opcionales en aras de contribuir al logro de la necesaria flexibilidad de la propuesta realizada.

Palabras clave: balance social; indicadores; sector cooperativo de ahorro y préstamo; sectorial

RESUMO

Tanto na praxe como na academia, é reconhecida a contradição entre a função social da cooperativa mexicana de poupança e empréstimo como participante da economia social do país e a prática quase inexistente de apresentar informações não financeiras a seus participantes. Neste contexto, o objetivo deste estudo foi desenhar um sistema de indicadores para a elaboração do Balanço Social neste setor da economia social mexicana. A pesquisa realizada correspondeu a uma abordagem mista não-experimental, onde a metodologia Prisma foi aplicada com a técnica de análise de conteúdo, juntamente com métodos especializados, a técnica de questionário e estatística descritiva. O principal resultado alcançado foi a concepção de 91 indicadores contextualizados para o setor em estudo, onde foi endossada a necessidade de uma abordagem setorial em sua concepção para permitir a comparabilidade e a implementação de estratégias comuns para cooperativas de poupança e empréstimo no México, simultaneamente com uma classificação dos indicadores propostos em obrigatórios, complementares e opcionais, a fim de contribuir para a obtenção da necessária flexibilidade da proposta feita.

Palavras-chave: balanço social; indicadores; setor cooperativo de poupança e empréstimo; setor

INTRODUCTION

Numerous authors have ventured into the study of Social Balance (Alarcón Conde & Álvarez Rodríguez, 2020; Alfonso Alemán, 2013; Cobián Puebla et al., 2020; Colina & Senior, 2008; Espín Maldonado et al., 2017; Gorosito & López Domaica, 2018; Hernández Santoyo et al., 2009; Larrinaga et al., 2019; Ribas Boned, 2001; Tamayo Cevallos & Ruiz Malbarez, 2018; Valverde Marín et al., 2017), where it is appreciated that the Social Balance Sheet has been defined from a system, an instrument, an additional and voluntary accounting statement, a Social Statement, a tool, a report, an information and even a memory. However, regardless of the term, the essential thing is that it represents an information system on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) aimed at stakeholders.

For the purposes of this study, because it is a definition that is already contextualized to this sector, the Social Balance Sheet for the Mexican Savings and Loan Cooperative Sector is assumed to be: The Statement of Social Accounting of a voluntary nature that shows in quantitative and/or qualitative terms the performance and evolution of the level of compliance with the cooperative principles, the contribution to sustainable development and the fulfillment of social responsibility with respect to the goals established inside and outside the cooperatives. (Cobián Puebla et al., 2020, p. 352).

This definition considers the current trends of the sector and the demands of the current Mexican society as Mexico is a "Participant of the Global Compact" of the United Nations Organization. Therefore, it establishes three strategic axes in the preparation of the Social Balance:

In a previous study of eight methodologies for the elaboration of Social Balance Sheets in seven countries (Argentina, Cuba, Colombia, Spain, Ecuador, Mexico and Uruguay), a sectorial tendency in their elaboration was established, based on cooperative principles, with an increasingly mixed approach in the incorporation of other criteria.

Colina and Senior (2008) state that in order to elaborate a Social Balance, an established methodology should not be assumed (Global Reporting `GRI', the International Labor Organization `ILO', among others), but the tendency should be to develop systems of indicators that fully interpret the organizational reality to be evaluated and that start from the different characteristics of the organizations in terms of social reason, sector to which they belong, environment where they perform, among others.

This reflection is shared in part because, although it recognizes the need for contextualization to the different realities, this should be done with a sectoral approach that enables comparison between entities in the same sector and, consequently, the establishment of common policies and strategies.

Mexican Savings and Loan Cooperative Societies (Socap in Spanish) are non-profit financial intermediaries whose purpose is to carry out savings and loan operations among their members and are part of the social sector of the Mexican Financial System (SFM in Spanish). Their main objective is to contribute to the financial inclusion of the population in the communities in which they operate and to cooperate with the Federal Government, other institutions and the cooperative sector itself in the dissemination, delivery and administration of the support programs that are promoted. Accordingly, these cooperatives within the SFM play a fundamental role in financial and social inclusion, as well as in the achievement of the SDGs of the United Nations Agenda.

Currently, according to the Cooperative Protection Fund (Focoop, 2020), Mexico has more than 700 registered Socap that manage assets of more than $190,000,000,000,000.00 and integrate more than eight million members, which gives a vision of the scope of these organizations in the national territory.

By their very foundation, expressed in their values and principles, credit unions play an important role in the struggle for equity, inclusion, poverty alleviation and sustainable development.

Currently, in the Mexican national context, the following particularities stand out in this sector:

The existence of the following development trends: The increase of Socap regulated by the National Banking and Securities Commission (CNBV in Spanish), specialization in staff training, innovation with the incorporation of new services and products, financial inclusion and social responsibility, the role of financial intermediary willing to compete under market conditions with any other modality of financial company, sectoral specialization, the search for efficiency in the provision of services, evolving as a specialized banking model, the development of cybersecurity and transparency that maximizes its image as a trustworthy financial institution (Cobián Puebla & Campos López, 2020).

The regulation of this type of enterprise by the CNBV leads to greater control and transparency of operations, the preparation of financial and non-financial information and greater institutionalization.

Existence of regulations in the sector, where it is evident that there are no specific regulations related to the preparation of information of a social nature or any restriction for organizations in this sector to prepare Social Statements as part of Social Accounting.

Participation in strategic alliances is expanding, for which information of a different nature is also demanded, including social and environmental information.

There is increased competition with commercial banks, financial institutions that generally prepare their social responsibility reports and have the CSR Distinction granted by the Mexican Philanthropy Center, a civil association that promotes and articulates the philanthropic, committed and socially responsible participation of citizens, social organizations and companies to achieve a more equitable, supportive and prosperous society, being identified as an important source of reliable information on social responsibility in the country, which annually awards companies for their proven socially responsible actions, the CSR Distinction.

In addition to the above, there is a growing demand from society and stakeholders for these institutions to report on their financial inclusion and social responsibility actions.

In practice, only three of the Mexican Socap are declared by socially responsible certifying bodies and very few of them produce relevant information of a social nature inside and outside the organizations for their own management and for their stakeholders.

However, the following considerations stand out in relation to the Social Balance for the Mexican context:

In addition, the aforementioned law establishes among the functions of the Consultative Council for the Promotion of the Social Economy, belonging to the National Institute of Social Economy (governing body), the function of preparing the social balance sheet of the sector's organizations. However, no methodology, procedure or indication in this respect has been defined by this institution, nor could any publications of social balance sheets made by this institute be found. This situation has meant that few Mexican cooperatives provide social information to their stakeholders and within the organizations and that there are no standards established for this sector and, consequently, general international standards are used.

This situation causes a contradiction between the social function that, as part of the social economy sector, these organizations carry out in the country and the almost non-existent practice of drawing up Social Balance Sheets.

This contradiction underlies the main purpose of the study presented here, which is to design a system of indicators for the preparation of the Social Balance Sheet in the Mexican savings and loan cooperative sector.

The importance of this research lies in the fact that it provides this sector with a contextualized and flexible proposal of indicators for the elaboration of the same, with a sectorial approach that allows the comparability between the co-operative societies that integrate it and consequently the design of common strategies.

The scope is limited to the Mexican savings and loan cooperative sector.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study corresponds to a non-experimental research of mixed approach with the use of the techniques of content analysis, expert consultation, questionnaire and the application of descriptive statistics for which a three-step procedure was developed.

In step 1, the research team determined the indicators by the variables defined by each cooperative principle in a study prior to this research. For this, the Prisma Methodology was used with the technique of content analysis.

The following keywords were used to explore the databases and registers: social balance sheet, indicators, co-operative sector.

For the search of the publications, the Scopus and Emerging Sources Citation Index databases were selected, together with other Latin American databases where the indexing of journals from the region where the research is carried out is common, such as Scielo, Redalyc, DOAJ, as well as web pages and databases from this sector.

A total of 262 publications were identified, of which 151 were examined; 111 were excluded because they were duplicated in the databases or registers. In a second stage, 56 were excluded because there was no correspondence between the title and the objective of this study. Ninety-five publications were evaluated to determine their eligibility, where 53 were excluded because the analysis of the abstract showed that it did not correspond to the objective of this study and did not fully comply with the PRISMA 2020 Checklist. Finally, 42 full-text documents were evaluated.

A limitation of the research was the insufficient publication on the subject of the sector under study, so the use of experts and the review of existing methodologies tried to reduce this shortcoming.

The content analysis technique was used, which according to Marradi, Archenti and Piovani (2007), as cited in Díaz Herrera (2018), constitutes "a technique of interpretation of texts [...] that is based on procedures of decomposition and classification of these". The technique of content analysis is commonly used in scientific research, in the search for variables and indicators.

The main authors consulted include Ribas (2001); Colina and Senior (2008); Hernández et al. (2009); Alfonso (2013); Espín et al. (2017); Valverde et al. (2017); Gorosito and López (2018); Ministerio de Hacienda y Crédito Público (2020) and Cobián et al. (2020). A total of 127 indicators were determined, which were decanted to 94, distributed as follows by cooperative principles:

To the principle 1 corresponds to 19 indicators

To the principle 2 correspond to 12 indicators

To the principle 3 correspond to 11 indicators

To the principle 4 correspond to 15 indicators

To the principle 5 correspond to 17 indicators

To the principle 6 there are 2 indicators

And finally, 18 indicators correspond to principle 7.

Step 2 defined the elements to be considered in the design of the indicators where, based on the criteria of Rodríguez, Fernández and de Dios (2015), the following were established:

A technical sheet was prepared for each indicator with the elements determined for its design.

In step 3, the indicators designed were subjected to validation by expert criteria, with the understanding that an expert is characterized by an in-depth knowledge of the subject and has direct practical experience in that field of knowledge, which is why he or she has obtained recognition, both from academia and in praxis.

Experts are assumed to be Mexican professionals with extensive knowledge of the subject matter in question, with experience of 10 or more years in the Mexican savings and loan sector and with recognized prestige in the sector for their achievements and competencies.

Twenty-one experts participated in the study, of whom 33.3% (7) are PhDs and 52.4% (11) hold Master's degrees, with an average age of 45 years and an average professional experience of 18 years in the sector, as representative members, members of the Board of Directors, managers of savings banks, researchers, employees, consultants and advisors of the Mexican savings and loan cooperative sector.

Another limitation of the research was the number of experts since, although 30 professionals were invited, only 21 agreed to participate.

For the evaluation of the proposal of the 94 indicators, through the technical sheet elaborated by the experts, a Likert Scale questionnaire was applied, where the answers between 5 and 4 were assumed as valid.

The experts' response was processed by relative frequency through SPSS version 24.0, where it is assumed from Huh, Delorme and Reid (2006) that indicators with a frequency of 80% in the range of responses, between 5 and 4, are valid.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

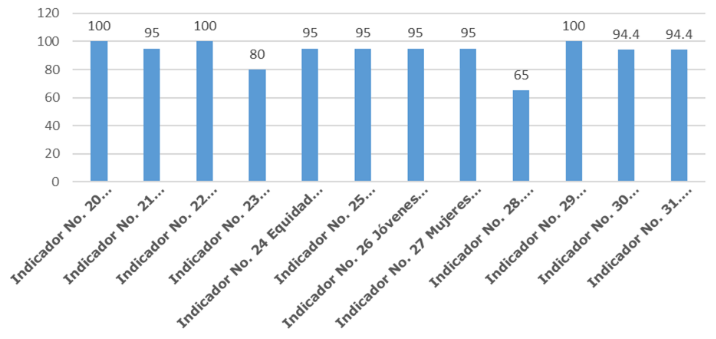

When the experts' responses were processed, it was found that of the 19 indicators proposed, corresponding to principle 1: Voluntary and Open Adherence, 18 were classified (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 - Social Balance Sheet Indicators for

Principle 1: Voluntary and Open Membership

Source: Own elaboration

This principle had four variables: Cooperative opening, voluntary exit, non-discrimination and social integrality. The first variable corresponded to the indicators growth of members, new members, growth of branches, number of states with branches of the co-operative and number of localities with operations of the co-operative, where a mainly communicational or informative intention is observed. The second variable is measured by the following indicators: Withdrawal of members and Withdrawal of members by causes, since for the management of the co-operative it is not enough to know the number of members who left, but the causes that led to this decision in order to draw up strategies.

In the third variable, six indicators are determined: Elderly adults Members, Junior Savers, Members by gender, Members by occupation, Members by sector and ethnic indicator (related to the participation of the country's ethnic minorities as members of the cooperative). In the indicators of this variable, it should be noted that, although they serve the purpose of visualizing the inclusive composition of the organization, they also provide important information to the internal administration for the design of products and services, taking into account the characteristics of its members.

The five indicators of the social integrality variable complement important information for the internal management of the co-operative by reporting on the average length of service of the members, average age of the member, generational replacement (measures the annual growth of the social base under 35 years of age to ensure compliance with equity and inclusion), the schooling of members and the number of branches by type of locality.

In relation to principle 2: Democratic management by partners, out of 12 proposed indicators, they ranked 11 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 - Indicators of the Social Balance of

Principle 2: Democratic Management by partners

Source: Own elaboration

This principle had three variables determined by the previous study: Participation in assemblies, Accessibility to positions and Work environment. In relation to the first variable, four indicators were determined: Participation in sectional conventions, representation of the branches in general assemblies, attendance at these assemblies and average interventions in assemblies, which seek to inform management of the level of participation and commitment of the members for their cooperative. In the second variable, 4 indicators were also determined: Gender equity in assembly, annual renewal of councilors, Youth and Women respectively in management positions that allow to evaluate how inclusive the co-operative is in its directive conformation; while the third variable through three indicators: Average seniority of employees, Employee satisfaction and Working conditions, informs the management about an important group of interest by the direct incidence that has in the growth and organizational development and the achievement of the objectives and goals traced.

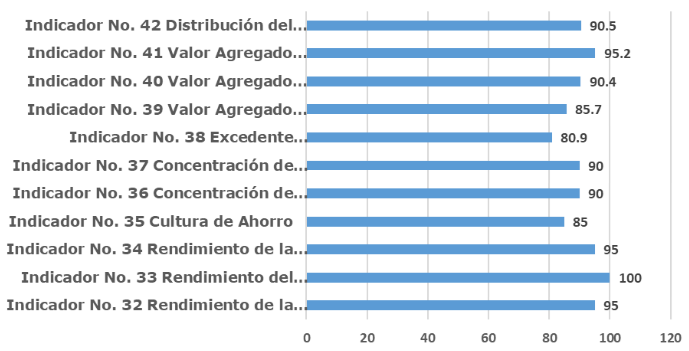

Principle 3: Economic Participation of Partners, with three previously identified variables, defined 11 indicators (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 - Indicators of the Social Balance of

Principle 3: Economic Participation of Members

Source: Own elaboration

In the variable capital as common property, six indicators were determined: Return on investment, Return on equity, Return on social contribution, Savings culture, Concentration of deposits and Credits respectively; while the variable allocation of surpluses is made up of a single indicator surplus distributed to the partners.

Finally, the co-operative value added variable with four indicators: Tangible, Intangible and Total co-operative value added respectively and Distribution of co-operative value added. Within these indicators, the intangible co-operative added value is of utmost importance, since it allows the stakeholders to visualize the non-accounting benefit that the member receives in savings by paying lower interest rates for the financial services or products received by the Co-operative and/or the increase of their benefits by offering them interest rates in savings and fixed-term investment, higher than the average of the financial institutions, together with discounts for prompt payment.

In principle 4: Autonomy and Independence, three variables are identified: Economic financial independence, Independence and transparency in information systems and Prevention of money laundering, financing of terrorism and other illicit activities (PLD in Spanish), where 14 indicators were determined (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 - Social Balance Sheet Indicators

for Principle 4: Autonomy and Independence

Source: Own elaboration

In the first variable, eight indicators are defined that measure that the cooperative is independent for its financial soundness (capitalization index, operational self-sufficiency, financial structure, funding of non-productive assets, coverage of non-performing loans, net credit, solvency and liquidity). In the second variable, an indicator is defined: Independence and quality of information, which measures observations made to the cooperative's information system and operating manuals, together with the analysis of the quality and independence of the information system.

The five indicators of variable three: PLD training actions, Employees trained in PLD, Compliance with PLD strategy, Unusual, Worrying and relevant operations detected and reported are of great importance and are reflected in the Social Report, since the prevention of money laundering and the fight against financing of terrorism constitute an integral strategy against organized crime of mandatory compliance for the financial institutions of the country.

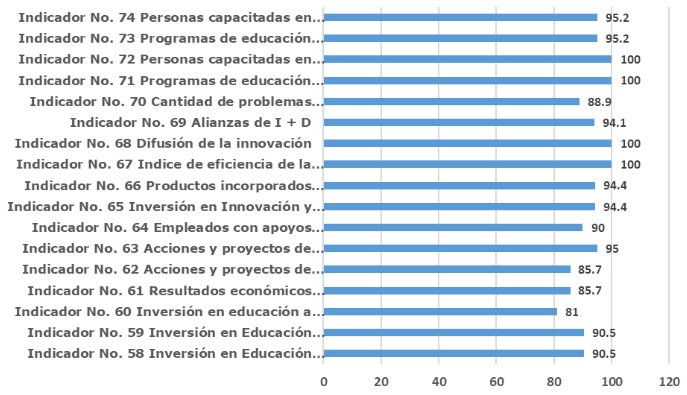

In principle 5: Education, Training and Information with its seven variables (investment in education, contribution to institutional development, output of education and training processes, communication and information, education and training for staff development, innovation and dissemination, co-operative education and financial education), 17 indicators were identified (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 - Social Balance Sheet Indicators

for Principle 5: Education, Training and Information

Source: Own elaboration

In the first variable, three indicators were defined (Investment in financial education, Cooperative education and Employees) which, by reporting the economic amounts allocated, give an image of the priority given by the cooperative to these activities. In the second variable, the indicator Economic results versus training was determined, which expresses how much the increase in savings, credit and investment is for each peso invested in training the co-operative's staff. In the third variable, the indicator Actions and projects of information and communication, executed with employees and managers, is defined. The fourth variable is made up of two indicators Training actions and projects carried out with the staff and the indicator Employees, with support for training.

The six indicators of the fifth variable (Investment in innovation and development; Products incorporated; Innovation output; Innovation efficiency index; Innovation diffusion; I+D alliances and Number of institutional problems solved by I+D) are of great importance because they express the sector's recognition of the current context, where innovation and knowledge are vital in the development of these organizations.

The last two variables related to the training and education of members and the general public on financial and cooperative issues allow to evaluate the level of informed decision making regarding the products and services to be consumed as an element of financial inclusion, together with the necessary understanding for them to assume the cooperative movement with all its values and principles. Two indicators were determined for each variable: Number of education programs carried out and number of people trained; within these, they are analyzed by categories (members, members' families and the general public).

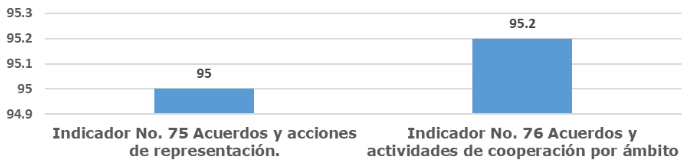

Principle 6: Co-operation between co-operatives with its two variables (integration for representative purposes and collaboration between co-operatives) defines two indicators (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6 - Social Balance Sheet Indicators

for Principle 6: Co-operation between Co-operatives

Source: Own elaboration

Since the National Cooperative Conflict in the nineties of the last century, it is recognized that the actions of collaboration, integration and representation between cooperatives in the sector have decreased, so only two indicators are defined that seek to inform stakeholders about the agreements and actions of representation of the Cooperative with the financial and cooperative sector, as well as the agreements and cooperation activities by area that the cooperative carries out in collaboration with other cooperatives in the sector.

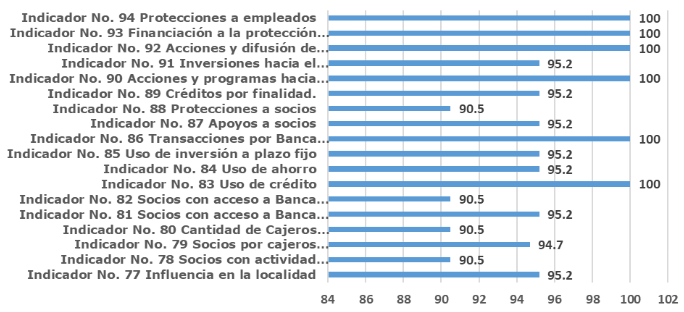

The last principle: Concern for the community has two variables: Improvement of the standard of living of members, employees and their families and support for community activities, where 18 indicators were determined (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 - Indicators of the Social Balance of

Principle 7: Interest in the Community

Source: Own elaboration

In the first variable, 13 indicators were determined: Members by ATMs, number of ATMs and credits by purpose.

The following indicators stand out for their social value and their impact on equity and financial and social inclusion:

In the variable Support to community activities, five indicators were determined: Actions and programs towards the community, Investments towards the development of communities, Actions and dissemination on environmental protection, Financing for environmental protection, and Employee benefits. This last indicator expresses the number and amounts of benefits to employees for different concepts that contribute to raising the standard of living of their families in the communities.

In relation to the classification of the indicators in correspondence to the obligatory nature of the calculation of each indicator, which is shown in the indicator type section of the technical sheet prepared, it is considered to be a very debatable problem in the design of indicators, highlighting the lack of authorial consensus in relation to the number of indicators. However, it is recognized that not everything can be measured, that the current management is increasingly complex and, consequently, the number of indicators must be sufficiently rational to make information and decision-making possible and not become an endless list that nobody uses, so this classification of indicators under compulsory criteria aims to obtain a sufficient but rational number to guarantee their use by the co-operatives' management.

Based on these considerations, the types of indicators to be considered for the Cooperative Social Balance Sheet are:

Depending on the method by which the information is obtained, two types of indicators are considered:

Of the 91 indicators designed, 48 are compulsory (52.7%), 25 are complementary (27.5%) and 18 are optional (19.8%). 34 (37.4%) correspond to the accounting method and 57 (62.6%) to the non-accounting method.

Regarding the second axis, 29 indicators (31.9%) are economic-financial indicators; 60 (65.9%) are social indicators and 2 (2.2%) are environmental indicators.

In relation to the third strategic axis, the indicators designed contribute to the fulfillment of SDGs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 10, 12 and 16.

Finally, it is agreed with Alfonso (2013, p. 187) that: Cooperatives, in their need to record, measure and evaluate their performance or social action, have the advantage conferred by their specificity as an enterprise, which makes it a peculiar and different organization from the rest and which is determined by its social commitment, both with respect to its members and with respect to other collectives interrelated with these organizations.

Therefore, the proposal of indicators designed provides this type of organization in Mexico with a contextualized instrumentation in accordance with its current needs for non-financial information requirements.

REFERENCES

Alarcón Conde, M. Á., & Álvarez Rodríguez, J. F. (2020). El Balance Social y las relaciones entre los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible y los Principios Cooperativos mediante un Análisis de Redes Sociales. CIRIEC - España. Revista de economía pública, social y cooperativa, (99), 57-87. https://doi.org/10.7203/CIRIEC-E.99.14322

Alfonso Alemán, J. L. (2013). Responsabilidad, gestión y balance social en las empresas cooperativas. Cooperativismo y Desarrollo, 1(2), 186-198. https://coodes.upr.edu.cu/index.php/coodes/article/view/61

Cobián Puebla, A., & Campos López, S. E. (2020). Una aproximación a los factores sociales en la elaboración del balance social en el sector cooperativo de ahorro y préstamo mexicano. Revista Visión Contable, (21), 102-119. https://doi.org/10.24142/rvc.n21a7

Cobián Puebla, A., Rosales Adame, J. J., & Fernández Andrés, A. (2020). Balance social cooperativo desde la perspectiva de la contabilidad social. Retos de la Dirección, 14(1), 337-362. https://revistas.reduc.edu.cu/index.php/retos/article/view/3512

Colina, J., & Senior, A. (2008). Balance social. Instrumento de análisis para la gestión empresarial responsable. Multiciencias, 8(No Extraordinario), 71-77. https://produccioncientificaluz.org/index.php/multiciencias/article/view/16724

Díaz Herrera, C. (2018). Investigación cualitativa y análisis de contenido temático. Orientación intelectual de revista Universum. Revista General de Información y Documentación, 28(1), 119-142. https://doi.org/10.5209/RGID.60813

Espín Maldonado, W. P., Bastidas Aráuz, M. B., & Durán Pinos, A. (2017). Propuesta metodológica de evaluación del balance social en asociaciones de economía popular y solidaria del Ecuador. CIRIEC - España. Revista de economía pública, social y cooperativa, (90), 123-157. https://doi.org/10.7203/CIRIEC-E.90.9240

Focoop. (2020). Boletín Informativo. Fondo de Protección Cooperativo. https://focoop.com.mx/website16/webforms/Boletin.aspx

Gorosito, S. M., & López Domaica, J. (2018). El balance social, cambios y actualidad. FACES, 24(50), 9-26. http://nulan.mdp.edu.ar/2869/

Hernández Santoyo, A., Pérez León, V., & Alfonso Alemán, J. L. (2009). La gestión y el balance social en la empresa cooperativa cubana. Caso de estudio: CPA 14 de junio. Contabilidad y Auditoría, (29), 62-78. https://ojs.econ.uba.ar/index.php/Contyaudit/article/view/70

Huh, J., Delorme, D. E., & Reid, L. N. (2006). Perceived third-person effects and consumer attitudes on preventing and banning DTC advertising. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 40(1), 90-116. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23860563

Larrinaga, C., Moneva, J. M., & Ortas, E. (2019). Veinticinco años de Contabilidad Social y Medioambiental en España: Pasado, presente y futuro. Revista Española de Financiación y Contabilidad, 48(4), 387-405. https://doi.org/10.1080/02102412.2019.1632020

Ribas Boned, M. A. (2001). El balance social como instrumento para la evaluación de la acción social en las entidades no lucrativas. CIRIEC - España. Revista de economía pública, social y cooperativa, (39), 115-147. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=307987

Rodríguez Pérez, H., Fernández Andrés, A., & de Dios Martínez, A. (2015). Análisis del presupuesto de las universidades: Un nuevo enfoque. Cofín Habana, 9(1), 1-10. http://www.cofinhab.uh.cu/index.php/RCCF/article/view/173

Secretaría de Servicios Parlamentarios. (2012). Ley de la Economía Social y Solidaria. Reglamentaria del párrafo octavo del artículo 25 de la Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, en lo referente al Sector Social de la Economía. Diario Oficial de la Federación. http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LESS_120419.pdf

Superintendencia de la Economía Solidaria. (2020). Informe del Balance Social y Beneficio Solidario (Circular Externa No. 09). Ministerio de Hacienda y Crédito Público. República de Colombia. http://www.supersolidaria.gov.co/sites/default/files/public/data/circular_externa_no._09_-_informe_del_balance_social_y_benenficio_solidario.pdf

Tamayo Cevallos, C. D., & Ruiz Malbarez, M. C. (2018). De la responsabilidad social empresarial al balance social. Cofín Habana, 12(1), 304-320. http://www.cofinhab.uh.cu/index.php/RCCF/article/view/293

Valverde Marín, E. L., Campoverde Bustamante, R. Y., Peña Vélez, M. J., & Vallejo Ramírez, J. B. (2017). Propuesta de un modelo de balance social para entidades financieras de la economía popular y solidaria en el Ecuador. En A. G. Vega Delgado (Ed.), Experiencias de investigación en ciencias administrativas y económicas en américa latina: Una perspectiva desde diferentes proyectos (pp. 183-200). UIDE. https://repositorio.uide.edu.ec/handle/37000/2525

Conflict of interest:

Authors declare not to have any conflict of interest.

Authors' contribution:

Áaron Cobián Puebla and Ana del Carmen Fernandez Andrés designed the study, analyzed the data and prepared the draft.

Jesús Juan Rosales Adame was involved in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data.

All the authors reviewed the writing of the manuscript and approve the version finally submitted.