https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9109-1339

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9109-1339 eylinjorgec93@gmail.com

eylinjorgec93@gmail.com

Cooperativismo y Desarrollo, May-August 2021; 9(2), 379-402

Translated from the original in Spanish

Determining factors of training in Cooperatives

Factores determinantes de la capacitación en Cooperativas

Fatores determinantes da formação em Cooperativas

Eylin Jorge Coto1; Angel Eustorgio Rivera2

1 Instituto Politécnico Nacional. México.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9109-1339

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9109-1339

eylinjorgec93@gmail.com

eylinjorgec93@gmail.com

2 Instituto Politécnico Nacional. México.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5636-9825

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5636-9825

angeleust@gmail.com

angeleust@gmail.com

Received: 12/12/2020

Accepted: 29/04/2021

ABSTRACT

The study of the behavior of cooperative societies has aroused the interest of researchers from all latitudes, since they place people as key actors in collective development. Like other organizations, cooperatives face financial situations, human talent management, etc., which affect their level of competition with respect to the market in which they operate. The International Cooperative Alliance establishes training as the fifth cooperative principle and the theory reflects that this constitutes a key element in the development and survival of cooperatives. However, the literature supports that this phenomenon has been less addressed in the Mexican context. Therefore, the objective of this research was to identify the factors that affect the training process in cooperatives in Mexico City. The study was qualitative and used the semi-structured interview as the main instrument for gathering information, as well as theoretical categorization to define the resulting elements. The findings of this research allowed the identification of five factors that determine the dynamics of the formation process: the intention of the partners to share knowledge, the availability of time, the level of organizational maturity, the provision of specialized courses and the need to balance knowledge in training activities.

Keywords: factors; human talent management; cooperative principle; training process; knowledge transfer

RESUMEN

El estudio del comportamiento de las sociedades cooperativas ha despertado interés en investigadores de todas las latitudes, debido a que sitúan a las personas como actores claves del desarrollo colectivo. Al igual que otras organizaciones, las cooperativas se enfrentan a situaciones financieras, de gestión del talento humano, etc., que afectan su nivel de competencia respecto al mercado donde se sitúan. La Alianza Cooperativa Internacional establece la capacitación como el quinto principio cooperativo y la teoría refleja que este constituye un elemento clave en el desarrollo y supervivencia de las cooperativas. No obstante, la literatura sustenta que este fenómeno ha sido menos abordado en el contexto mexicano. Por ello, el objetivo de la presente investigación consistió en identificar los factores que repercuten en el proceso de capacitación en las cooperativas de la Ciudad de México. El estudio fue de corte cualitativo y utilizó a la entrevista semiestructurada como principal instrumento de recopilación de información, así como la categorización teórica para definir los elementos resultantes. Los hallazgos de esta investigación permitieron la identificación de cinco factores que determinan la dinámica del proceso de formación: la intención de los socios de compartir conocimiento, la disponibilidad de tiempo, el nivel de madurez organizacional, la provisión de cursos especializados y la necesidad de equilibrar el conocimiento en las actividades de capacitación.

Palabras clave: factores; gestión del talento humano; principio cooperativo; proceso de capacitación; transferencia de conocimiento

RESUMO

O estudo do comportamento das sociedades cooperativas despertou o interesse de investigadores de todas as latitudes porque colocam as pessoas como atores-chave no desenvolvimento coletivo. Tal como outras organizações, as cooperativas são confrontadas com situações financeiras, gestão de talentos humanos, entre outras, que afectam o seu nível de competência em relação ao mercado em que operam. A Aliança Cooperativa Internacional estabelece o desenvolvimento de capacidades como quinto princípio cooperativo e a teoria reflete que é um elemento chave para o desenvolvimento e sobrevivência das cooperativas. No entanto, a literatura apoia que este fenómeno tem sido menos abordado no contexto mexicano. Por conseguinte, o objetivo desta investigação era identificar os fatores que afectam o processo de formação em cooperativas na Cidade do México. O estudo foi qualitativo e utilizou a entrevista semiestruturada como principal instrumento de recolha de informação, bem como a categorização teórica para definir os elementos resultantes. Os resultados desta investigação permitiram a identificação de cinco fatores que determinam a dinâmica do processo de formação: a intenção dos parceiros de partilhar conhecimentos, a disponibilidade de tempo, o nível de maturidade organizacional, a oferta de cursos especializados e a necessidade de equilibrar os conhecimentos nas atividades de formação.

Palavras-chave: fatores; gestão de talentos humanos; princípio da cooperação; processo de formação; transferência de conhecimentos

INTRODUCTION

The Rochdale Equitable Pioneers Society represents an icon for the global cooperative movement (Martínez Charterina, 2015). Recognized as the first successful case of this type of organization and influential in the change of the labor paradigm due to the vision of association based on mutual aid and equitable, as well as fair distribution of the profits obtained.

With the evolution of history, the need to formalize and define guidelines in the management of this type of economic and social entity increased; therefore, the International Cooperative Alliance was created. This organization is a benchmark for cooperativism at the international level (Martínez Charterina, 2015). However, the concepts of cooperativism have been implemented in Latin American countries through internal legislative mechanisms (Cracogna, 2009). In Mexico, the first recognized legal articulator was the Code of Commerce of 1890, evolving gradually until reaching the current General Law of Cooperative Societies of 1994 (Izquierdo Muciño, 2009).

According to Article 2 of Mexico's General Law of Cooperative Societies, a cooperative society constitutes "a form of social organization made up of individuals (...), with the purpose of satisfying individual and collective needs, through the performance of economic activities of production, distribution and consumption of goods and services".

Other elements that characterize cooperative societies are equality of conditions with respect to collective decision-making, solidarity and democracy. Likewise, these organizations tend to organize themselves in networks, creating an environment of mutual aid, which encourages the development of the cooperatives with which they are related and provides a boost to the cooperative movement (Seguí Mas, 2011). All this is modeled by the principles: voluntary and open membership, democratic management, economic participation of members, autonomy and independence, education, formation and information, cooperation between cooperatives and interest in the community.

In addition, these types of organizations promote a greater commitment of the members to the activities they carry out and to the labor collective, which has a positive impact on the consolidation of organizational values. In addition, cooperatives generate sources of employment under the principle of achieving more dignified work, which allows for equitable benefits for members.

However, like any other organization, cooperatives must also face complex situations in order not to perish in the competitive markets in which they operate. Several authors (Ali et al., 2018; Izquierdo Muciño, 2009; Seguí Mas, 2011) have identified different tangible aspects that influence the failure of cooperatives; among them: the formation of members, decapitalization due to the voluntary withdrawal of some of the members, business management, the impossibility of valuing profitability, the lack of formation and information to distinguish between cooperative activities (internal) and social purpose (external) and the evident lack of specialization, division and organization of work.

Formation, one of the elements previously mentioned, is considered one of the key activities in the management of human talent (Karim, 2019), being human capital all the people who fulfill established functions within an organization. Consequently, its proper management is aimed at developing activities that promote the use and development of human qualities and, in turn, enable these qualities to become a source of sustainable competitive advantage for the organization. Therefore, Collins (2021) states that human talent management plays a decisive role in the performance of organizations.

In this sense, training is identified as a process that aims to prepare, develop, raise awareness, train and teach all the people who need it to perform in a certain job (Carreño Villavicencio et al., 2020). Therefore, it is aimed at improving the competencies of each individual, in order to achieve their maximum performance (Bell et al., 2017). Likewise, training is considered a strategic tool when the objectives of the organization and the specific needs of the collaborators are aligned.

On the other hand, the learning process within the various forms of organization is based on the processes of creation, transfer and use of knowledge by employees. In this sense, Spraggon and Bodolica (2012) mention training programs as forms of knowledge transfer.

Knowledge transfer among actors in a given context is influenced by factors that enable and inhibit that process. According to Vaghefi, Lapointe and Shahbaznezhad (2018), barriers can be grouped into four sets. The first, related to knowledge, is linked to the complexity of the information to be transferred and the degree of understanding between participants. The second, related to knowledge sharing, where the level of credibility and communication skills among the parties involved influence. The third is linked to the receiver and sender of knowledge. In this case, the lack of absorption capacity and the lack of motivation of the actors are elements to be considered. Finally, related to the organization, there are elements such as organizational culture and structure. On the other hand, among the knowledge enablers, the following can be mentioned: the sender's skills to transmit knowledge, the motivation of those involved, the closeness of relationships and a supportive organizational culture (Vaghefi et al., 2018).

In the context of cooperative societies, training and knowledge transfer are fundamental elements to develop technical skills, as well as fostering respect for cooperative principles, values and philosophy in general. In addition, formation has boosted the improvement of the performance of this type of organizations by increasing the competencies and preparation of members (Anania & Rwekaza, 2018; Macías Ruano, 2015). Therefore, Kinyuira (2017) asserts that the fifth principle, education, formation and information, is the most important and basic of the rest, since he considers it fundamental for the continuity of the cooperative movement.

According to Article 7 of the Regulations of the International Cooperative Alliance, one of the principles governing the operation of cooperatives is to provide and strengthen the education, formation and information of cooperative members. That is why the nature and dynamics of the training process is fundamental to analyze and evaluate the performance of these economic and social units (Sosa González et al., 2019). In this sense, Rojas (2010) points out that research on cooperative education in Mexico presents marked deficiencies; among them, the scarcity of studies related to this topic and the low motivation on the part of cooperatives to collaborate in research. However, cooperative societies are becoming increasingly important in the labor, economic and social environment, which is why Montañez (2017) recognizes the important role played by academic institutions in the development of the cooperative movement.

Consequently, the objective of this study was to identify the factors that affect the training process in cooperatives in Mexico City, in order to reduce the information and knowledge gap between theory and practice in this field of study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The research is qualitative with an exploratory-descriptive scope and has the objective of identifying the factors that influence the training process. The methodological strategy of the multiple case study (Yin, 2003) was used. Five cooperatives in Mexico City were selected; non-probabilistic convenience sampling was followed (Tracy, 2013). This implied the main limitation of the present study, since the cases were selected due to access to information and given the researchers' approach to these case studies (Tracy, 2013).

Respecting the classification offered by the General Law of Cooperative Societies of the selected organizations, two are producers of goods, two are producers of services and the last one is classified as a consumer of goods. Four of the organizations are relatively young with incorporation date between 2016 and 2017. Only one of them has more experience in the cooperative context, referring that its date of conformation was in 2007. These characteristics are summarized in table 1.

Table 1 - Comparison of the nature of the five selected cooperatives

Code |

Cooperative 1 |

Cooperative 2 |

Cooperative 3 |

Cooperative 4 |

Cooperative 5 |

Classification |

Service producers |

Producers of goods |

Producers of goods |

Consumers of goods |

Service Providers |

What they do |

Journalism |

Elaboration of handmade chocolate. Promotion and dissemination of cocoa culture. |

Transformation of fresh food into dehydrated food. |

Consumption and distribution of organic agricultural products harvested by small producers. |

Integral professional accounting, architectural and legal services. |

Year founded |

2016 |

2017 |

2007 |

2017 |

2017 |

Number of members |

5 members and collaborators |

5 members |

5 members |

5 members and 1 collaborator |

5 members and collaborators |

Source: Own elaboration

The data collection technique used was the semi-structured interview, which allowed obtaining and analyzing the opinions and perspectives of the members of the cooperatives participating in the study (Tracy, 2013). The interviews were conducted at the home of each of the cooperatives, during the months of December 2019 and January 2020; they had an average duration of 45 min. for each participant in the study. Before conducting each of the interviews, the participants were asked for permission to record them and were told that, in case they did not want to answer any question, they should let them know at the time in order to continue with the rest of the questions. All the interviewees showed great willingness during the interviews and even commented that, if additional information was required, they would be contacted again.

Respecting the request of the cooperatives and following the principle of anonymity (Abad Miguélez, 2016) that allows safeguarding the identity of the participants contributing to the study, the names of the participating organizations are not mentioned. For this reason, the organizations were coded as follows: Cooperative 1, Cooperative 2, Cooperative 3, Cooperative 4, and Cooperative 5.

All interviews were recorded and fully transcribed. The text processor Word was used for the transcription and organization of the evidence collected and a document was generated for each cooperative interviewed. In each document, the lines were numbered in a continuous manner, in order to specify the location of the information. Consequently, the format of Cooperative 1, L01-L10, was followed, which implies that the information is provided by Cooperative 1 and is located between lines 1 and 10. The content of the interviews was analyzed and a theoretical categorization of the elements found in them was made (Tracy, 2013).

Since the participating organizations gave their consent to use all the information obtained in the interviews, the data shown in this research are those collected directly from the cooperative members.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Although the literature regarding the training process in cooperatives and the identification of factors that inhibit and enable such process is limited, there are some studies (Anania & Rwekaza, 2018) that agree on the importance of the formation activities and the definition of elements that hinder the development of the same.

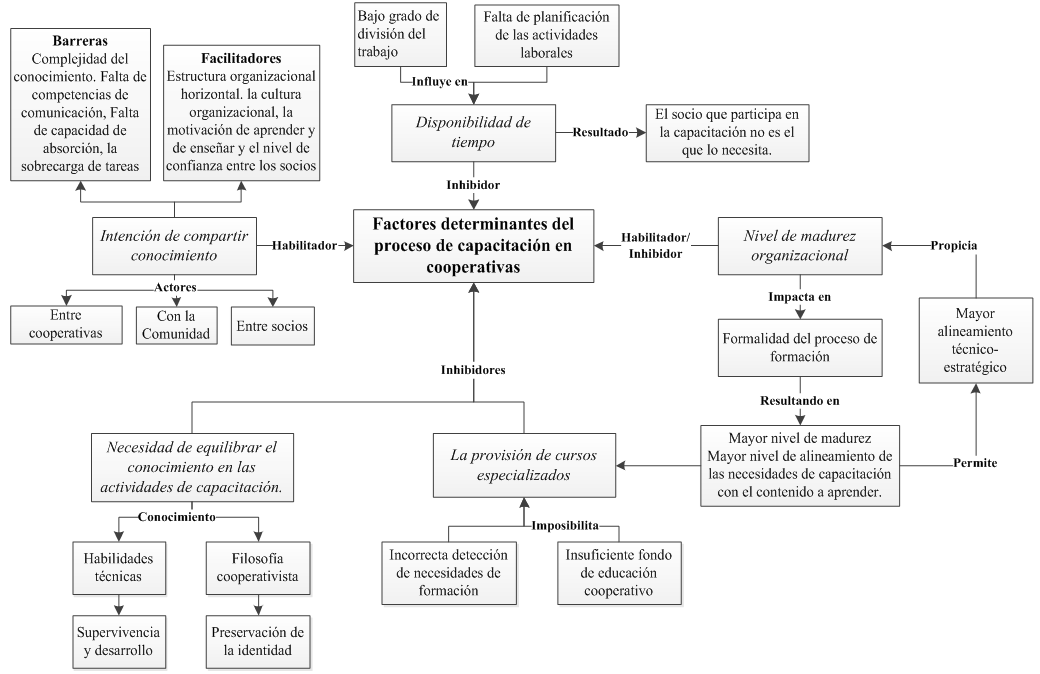

In that sense, the findings of this research were presented considering as a priority the identification of the factors that influence the outcome of the formation process in cooperatives: (1) intention of members to share knowledge, (2) availability of time, (3) level of organizational maturity, (4) the provision of specialized courses, and (5) need to balance knowledge in training activities. Also, with the support of Figure 1, the relationship among the identified factors is visualized.

Fig. 1 - Influence of factors in the training process in cooperatives

Source: Own elaboration

Determining factors of training of cooperatives

In the information gathered, five elements that influence the results of the formation process in the cooperatives stand out. These factors are listed in Table 2, which details their concepts and classifies them as enablers or inhibitors of the training process.

Table 2 Identified factors, concept and classification

Factor |

Concept |

Classification |

Intention of the partners to share knowledge |

This element is defined as the willingness of cooperative members to share knowledge, inside and outside the organization, with the objective of promoting continuous learning. |

Enabler |

Time availability |

The low degree of division and organization of labor represents a constraint on members' time availability, which restricts their participation in training activities. |

Inhibitor |

Organizational maturity level |

This factor explains a two-dimensional cause-effect relationship. The first duality is represented by the influence of the maturity of the members and of the cooperative on the formality of training management. Likewise, training is an aspect that favors the technical-strategic alignment of the organization. |

Inhibitor/ Enabler |

Provision of specialized courses |

It refers to the possibility of the cooperatives to participate in courses with a higher degree of specialization, in relation to the reduced cooperative education fund they have. |

Inhibitor |

Need to balance knowledge in training activities. |

This element refers to the lack of provision of training that complements the cooperative philosophy with technical-administrative knowledge. |

Inhibitor |

Source: Own elaboration

Intention of the partners to share knowledge

Knowledge can be created, formalized and shared within and among organizations, which is proven in the present research, where the participating cooperatives expressed that knowledge transfer happens as a spontaneous and continuous process: "...all the time we are transferring knowledge from one to another..." (Cooperative 1, L286). However, it is noteworthy that, even though the organizations interviewed share the same nature, the dynamics regarding transfer vary among them.

On the other hand, three main pairs of actors were identified in the transfer process: members belonging to the same cooperative, members of different organizations and cooperatives with society. In the first case, information beneficial to the development of the cooperative is shared among agents belonging to the same context. However, the nature of the knowledge may vary. An example of this was found in the behavior of Cooperative 5, which assures that members do not share knowledge related to their professional profile due to the difference in the work they perform (accountants, lawyers, auditors and architects).

The second classification refers to the transfer dynamics involving actors belonging to different environments. It consists of sharing relevant knowledge among cooperative members, the organizations involved being in mutual agreement.

Finally, with respect to the interaction of the cooperatives with society, the example of the fourth organization interviewed was highlighted. In this case, the work philosophy they share, "good living", is promoted both among the organization's participants and in the community where it operates. In this way, they provide knowledge about the positive aspects of healthy eating: "...in the sales area there is a colleague who explains everything about the product, as they are natural products, we must expose the benefits of each one to the community" (Cooperative 4, L166-L168).

In general, the interviewees state that knowledge sharing is considered an influential element in their development. Some of the benefits cited are the identification of projects of interest to the organization; the development of new skills, knowledge and attitudes; the promotion of a culture based on camaraderie among participants; the alignment of organizational and personal interests; and the development of a work philosophy based on the principles of cooperativism.

In this sense, García, García and Figueras (2018) reaffirm that the transfer of knowledge within cooperative societies and with other actors with whom they relate is an inherent characteristic in the performance of such organizations. This is due to the influence of the principle of mutual aid, solidarity and their group nature. Therefore, the transfer of knowledge is not only a factor in which cooperatives can help themselves to define and develop a path to continuous improvement, but also influences the strengthening and respect of the cooperative philosophy, in order to give continuity to the international movement.

On the other hand, García, García and Figueras (2018) highlight that sharing knowledge promotes and consolidates the learning of cooperative principles. However, these authors do not consider the intention, motivation and skills of the members to transmit and receive such knowledge as determining elements in the outcome of the formation process.

Consequently, knowledge transfer is considered a positive factor for learning and, specifically, for training processes in cooperative societies. However, the transfer process is influenced by positive and negative elements, which have been described in the theoretical analysis of this study as enablers and inhibitors.

In this sense, the following are identified as facilitators: the horizontality of the organizational structure of the cooperatives, the culture, the motivation to learn and to teach, and the level of trust among members. Likewise, elements that diminish the effectiveness of the transfer are identified, among them: the level of complexity of the members' tacit knowledge, the lack of communication skills, the lack of absorption capacity, the overload of tasks of the people involved, and the difficulties in the codification of tacit knowledge.

Availability of time

The literature exposes that time availability constitutes one of the elements that limit the provision of training in cooperatives (Anania & Rwekaza, 2018). The same criterion can be homologated in the present study. However, there are other reasons why cooperative members do not participate in the formation actions they need; among them, the minimal level of division of labor that characterizes the behavior of these organizations (Seguí Mas, 2011).

In this sense, the interviewees confirm that this situation favors their participation in more than one process, in order to cover the needs of the economic entity, which causes an increase in the level of individual work: "(...) the activities exceed the people; therefore, many times a person has to perform more than one function. One person is in two or three areas" (Cooperative 4, L92-L95).

On the other hand, the lack of mention and evidence that these organizations manage their work time with the support of agendas or plans hinders the possibility of glimpsing what part of the working day can be devoted to participate in relevant training processes. Thus, cooperative members cite lack of time availability as a cause of their absences to formation activities. However, this performance could be improved by organizing and defining the times and tasks to be performed by each participant, without losing sight of the importance of collective work and the principles of mutual help among members.

However, the lack of work plans leads to imprecision in the use of time resources by the partners; the availability of time in itself also has a negative effect on the formation process.

The situations described above result in the current practice: the member who participates in training activities is not the person who really needs to develop competencies related to their work activities, but the one who is considered to have more time available to participate. In this way, it was confirmed in the evidence collected: "(...) one of the members of the cooperative receives the invitation and we decide who has the time to go" (Cooperative 1, L229-L230). Thus, this factor has an impact on the discrepancy among the participants in the training actions and the cooperative members who do need to develop competencies to be able to offer better results to the labor collective.

Likewise, cooperatives are equally identified by the scarcity of financial resources. If it is added to this this erroneous behavior: paying for training for people who do not need it. This causes a waste of this limited resource and training loses its investment character, given the low probability of obtaining benefits. This is an example of how cooperatives threaten their survival.

Organizational maturity level

When analyzing the organizational evolution of the five case studies, it can be seen that they have undergone a constant process of reconstruction. This transition process, in which the partners are immersed, goes from their participation in a labor collective, where the rules and tasks of each person were well established, to having to create from scratch a work system based on cooperativism. Consequently, it will be necessary to uproot the paradigms related to the logic of the operation of a capitalist company to include elements of social and solidarity economy.

In this new organization that they are beginning to create, all members have the same right of decision and influence. It becomes a challenge to reconcile their personal expectations about the cooperative philosophy with the primary objective, which implies that the economic entity should be profitable enough not to perish.

In addition to all the complex changes mentioned above, it was observed that the people who join this type of organization are sometimes not experts in administrative disciplines and are forced to learn for the common good: "I manage the finances of the cooperative, but I need a course in accounting" (Cooperative 2, L153-L155). An example of this is the case of Cooperative 2, where the colleague who is in charge of the accounting-financial work of the organization has as her basic formation a Bachelor's degree in Psychology.

Under these conditions, it is evident that an endless number of concerns arise, which cause the partners to have doubts and, sometimes, even confusion. It is then that, through a process of trial and error, they begin to mature their concepts, to structure and define themselves as an organization, to establish objectives, to identify their vision and to define areas of opportunity in a concrete manner.

In these early stages of organizational development, the cooperative members recognize training as a necessary tool to achieve better performance: "(...) training has given us more order and discipline" (Cooperative 4, L198). However, they are stranded at a point where they consider that everything they can learn will have a positive impact, without reflecting on what elements they really need to develop.

As the organization consolidates, the members develop a greater capacity to recognize that not every type of formation implies a benefit. They have forged solid criteria that allow them to discern which activities are convenient to participate in and which are better to avoid: "little by little you realize what you need and what you don't need" (Cooperative 3, L292).

In the next stages of development, uncertainties continue to arise, however, the cooperatives have reached a higher level of business maturity that results in greater stability and better structuring of their internal processes. "To the cooperative, it has given more structure (referring to training), because before they worked in chaos. Not even a work plan. 2019 was the year in which there was already an annual planning in form, with objectives" (Cooperative 2, L179-L181). This behavior allows them to make more accurate decisions, including the training process. Therefore, formation goes from being an element that solves emergencies to a strategic process that allows the detection of projects and new ideas that will have repercussions in the medium and long term.

For their part, Sosa et al. (2019) highlight training as a fundamental element in social enterprises in Mexico and in the survival of cooperatives in the markets where they are located. Accordingly, in the framework of the present research, it was found that members recognize the countless benefits that come from formation. However, the formal nature of training as a guarantee of quality of the desired results was not addressed by Sosa et al. (2019), nor was the influence of organizational development on the training process.

In this sense, Anania and Rwekaza (2018) explain that the formality with which the learning needs detection activity is carried out affects the performance of the formation process. More, formal training development does not only involve learning needs detection. In addition, activities such as planning, execution and evaluation of results must be considered (Karim, 2019).

In this regard, in the entities interviewed, the development of the formation depends on the skills of the cooperative members to face such activity; therefore, informality in training was a characteristic present in all the organizations. Likewise, the freedom given to manage the training process is considered counterproductive because the formation should aim at a clear objective that allows tangible results, both for the professional development of the members and for the collective improvement as an economic and social entity.

Finally, this research not only considers the influence of training on the development of organizations, but also how the maturity achieved by the cooperatives allows for more expert decision making with respect to the formation processes. Therefore, training has an influence on organizational development and the structuring of internal processes. Accordingly, the maturity of the cooperative in its broadest sense has an impact on formality and the reduction of errors throughout the formation process.

Provision of specialized courses

The provision of specialized courses is influenced by two main elements: the incorrect detection of formation needs and insufficient financial resources in the cooperatives. The first of these, in turn, is related to the informality of the training process. This behavior leads to a misalignment between the needs expressed and the content and degree of specialization of the training, which leads to a decrease in the benefits attributed to the formation.

However, as cooperatives reach a higher degree of maturity, stability and sustainability, they define more precisely the elements to be developed in order to continue improving their economic indicators. In the area of training, this translates into the use and structuring of formation plans, which provides this process with a higher level of organization and formality.

This is why the training in which they initially participated is no longer sufficient to follow up on the process of organizational maturity and growth: "(...) we need a little more advanced training" (Cooperative 3, L268). At this point, the cooperatives require formation activities with a higher degree of specialization to guarantee the expected results. However, in order to have access to specialized training, they must have a cooperative education fund to support such formation needs, given that there is a low probability of being able to participate in this type of courses for free: "free training that we can receive, yes, but it does not meet our expectations" (Cooperative 5, L98-L101).

In this sense, Anania and Rwekaza (2018) state that the scarcity of monetary resources represents a limitation for the provision of training in general. However, the difference in the results of the present research, with respect to the previously cited study, is that the cooperative members indicate that it is possible for them to access free training from universities and government institutions. However, on many occasions, these activities do not meet the learning needs in specialized topics that would allow them to continue raising the development curve of their organizations.

Consequently, it is a reality that cooperatives are characterized by the scarcity of financial resources, which limits access to more specialized formation methods. This is why these organizations must allocate their budget to formation activities that minimize the shortcomings of the economic unit and guarantee their permanence in the market where they are located.

Need for knowledge balance in training activities

In the theory, it was evidenced, regarding the formation process, the need and importance of harmonizing the development of skills, acquisition of new knowledge and change of attitudes with the cooperativism philosophy (García Pedraza et al., 2018; Kinyuira, 2017). However, the definition of this factor arises from the aforementioned gaps in training provision characterized by balancing technical skills, such as: marketing, finance, accounting, among others, with the base philosophy of this type of organization. Therefore, interviewees assert the difficulty of participating in specialized courses that equitably link both ideas.

"The training we have taken, which has helped us, does not focus on the social and solidarity economy (...) And, on the other hand, the training we have taken on the social and solidarity economy of cooperativism does not give weight to the economic part. So, this is the balance that we have found difficult to integrate". (Cooperative 2, L196-L224)

The organizations interviewed show their interest in defining and preserving their identity with the support of talks and by participating in events that promote the cooperativism philosophy. Ideas supported by those of Gaminde and Martínez (2019), who affirm the need to maintain cooperative education based on the principles and values promoted by the international cooperative movement as a guarantee for its continuity.

However, sometimes this type of training neglects basic administrative activities, which are a fundamental pillar for the development of organizations. They also forget the importance of indicators such as profitability, which is a guarantee of the economic entity's permanence in the market where it competes. Accordingly, the interviewees mention that some cooperatives opt for a perspective based purely on the social economy: "(...) we observe that many fellow cooperative members feel a kind of itch for cooperatives to be treated as businesses and for them to relate to business matters" (Cooperative 1, L221-L224). However, Sosa et al. (2019) have found that the lack of formation in economic-financial, strategic and management aspects in cooperative societies are causes of mortality in these organizations.

It is obvious the conflict that may arise from choosing a course or workshop where the basic pillars of cooperatives do not coexist: business administration issues and knowledge about cooperative philosophies. But, if this duality is ignored, the survival and/or the essence of this type of organization is endangered.

The results presented have their main limitation in the size of the selected sample. For this reason, the present research is considered a first attempt to guide cooperatives on the path of good training management practices. This is due to the fact that, in the cooperatives interviewed, this process is far from being considered formal, which, to a large extent, is due to the limited skills and knowledge that the members have to develop this activity.

Consequently, there is a need to understand and identify factors that influence the outcome of the formation process. It is also necessary to recognize the strategies that increase the positive influence of the enablers and limit the effects of the inhibitors, in order to promote the growth of cooperative societies.

In this sense, elements such as the intention of members to share knowledge, both within their organization and between cooperatives, is a positive aspect that favors the development of economic and social entities. Therefore, this factor is considered an enabler of the formation process. However, it is necessary to consider that within the transfer process itself there are barriers and facilitators. Therefore, it is of interest to identify and manage both categories to counteract the effects of the inhibitors with the support of the identified enablers.

Secondly, the availability of time and the provision of specialized courses have been recognized as inhibitors of the training process. However, the negative influence of both elements can be diminished through better organization and planning of internal processes in the cooperatives. Among these are: planning the budget for training and a conscious detection of learning needs.

Another factor, the level of organizational maturity, explains how the development achieved by the cooperative influences the decisions and results of the formation process. As cooperative members develop their work skills and the organization consolidates, training will take on a more formal character. Therefore, this element can be conceived as an enabler or inhibitor of the training process, depending on its positive or negative impact.

The last factor identified highlights the need to balance technical-administrative knowledge with the cooperativism philosophy in the content of training courses. One of the recommendations derived from this point consists of relying on government organizations and universities to create, disseminate and promote formation activities where both contents are included and weighed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACyT in Spanish) for its financial support and the organizations that offered to participate as primary sources of information.

REFERENCES

Abad Miguélez, B. (2016). Investigación social cualitativa y dilemas éticos: De la ética vacía a la ética situada. Empiria. Revista de metodología de ciencias sociales, (34), 101-120. https://doi.org/10.5944/empiria.34.2016.16524

Ali, M. J., Wenguang, G., & Jinhua, C. (2018). Comparative Analysis of Factors Affecting Farmers Cooperatives Development. Case Studies of Zanzibar-Tanzania and Baoding City of China. International Journal of Academic Multidisciplinary Research, 2(2), 1-12. http://ijeais.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/IJAMR180701.pdf

Anania, P., & Rwekaza, G. (2018). Co-operative education and training as a means to improve performance in co-operative societies. Sumerianz Journal of Social Science, 1(2), 39-50. https://www.sumerianz.com/pdf-files/sjss1(2)39-50.pdf

Bell, B. S., Tannenbaum, S. I., Ford, J. K., Noe, R. A., & Kraiger, K. (2017). 100 years of training and development research: What we know and where we should go. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 305-323. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000142

Carreño Villavicencio, D. V., Molina Quiroz, C. A., Granda García, M. I., & Mero Rosado, V. F. (2020). Gestión del talento humano en cooperativas de emprendimiento rural. CIENCIAMATRIA, 6(10), 585-597. https://doi.org/10.35381/cm.v6i10.234

Collins, C. J. (2021). Expanding the resource based view model of strategic human resource management. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(2), 331-358. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1711442

Cracogna, D. (2009). La legislación cooperativa en México, Centroamérica y el Caribe. Alianza Cooperativa Internacional para las Américas. https://repositorio.coomeva.com.co/handle/coomeva/2079

Gaminde Egia, E., & Martínez Etxeberria, G. (2019). Training of cooperative values as a decisive element in new jobs to be created by 21st century cooperatives. Boletín de La Asociación Internacional de Derecho Cooperativo, (54), 97-114. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7003349

García Pedraza, L., García Ruiz, J. G., & Figueras Matos, D. (2018). Importancia de la educación cooperativa. Una experiencia cubana. REVESCO. Revista de Estudios Cooperativos, 129, 142-160. https://doi.org/10.5209/REVE.62881

Izquierdo Muciño, M. E. (2009). Problemas de las empresas cooperativas en México que atentan contra su naturaleza especial. Boletín de la Asociación Internacional de Derecho Cooperativo, (43), 93-123. https://doi.org/10.18543/baidc-43-2009pp93-123

Karim, R. A. (2019). Impact of Different Training and Development Programs on Employee Performance in Bangladesh Perspective. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Research, 2(1), 8-14. https://doi.org/10.31580/ijer.v2i1.497

Kinyuira, D. K. (2017). Assessing the impact of Co-operative education/training on co-operatives performance. 5(1), 23-41. http://jspm.firstpromethean.com/documents/5-1-23-41.pdf

Macías Ruano, A. J. (2015). El quinto principio internacional cooperativo: Educación, formación e información. Proyección legislativa en España. CIRIEC - España. Revista jurídica de economía social y cooperativa, (27), 243-284. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5382997

Martínez Charterina, A. (2015). Las cooperativas y su acción sobre la sociedad. REVESCO. Revista de Estudios Cooperativos, 117, 34-49. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_REVE.2015.v117.48144

Montañez Moya, G. S. (2017). El papel de la Universidad en el emprendimiento de organizaciones solidarias cooperativas. Cooperativismo & Desarrollo, 25(111), 23-32. https://doi.org/10.16925/co.v25i111.1770

Rojas Herrera, M. E. (2010). Metodología para la educación cooperativa en México. Estado del conocimiento. Textual. Análisis del medio rural latinoamericano, 55(enero-junio), 83-106.

Seguí Mas, E. (2011). Factores determinantes en la predicción del fracaso empresarial en cooperativas: Un análisis Delphi. Centro de Investigación en Gestión de Empresas Universitat Politècnica de València. http://www.aeca1.org/pub/on_line/comunicaciones_xvicongresoaeca/cd/169i.pdf

Sosa González, J. L. S., Gómez Abad, P., Carmona Silva, J. L., & Medel Sánchez, J. M. (2019). Una aproximación empírica a la viabilidad de los emprendimientos sociales en México: El ciclo de vida de las cooperativas de la Región de la Costa de Oaxaca. REVESCO. Revista de Estudios Cooperativos, 131, 151-178. https://doi.org/10.5209/REVE.63564

Spraggon, M., & Bodolica, V. (2012). A multidimensional taxonomy of intra-firm knowledge transfer processes. Journal of Business Research, 65(9), 1273-1282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.043

Tracy, S. J. (2013). Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact. John Wiley & Sons. https://books.google.de/books/about/Qualitative_Research_Methods.html

Vaghefi, I., Lapointe, L., & Shahbaznezhad, H. (2018). A multilevel process view of organizational knowledge transfer: Enablers versus barriers. Journal of Management Analytics, 5(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/23270012.2018.1424572

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage Publications. https://www.worldcat.org/title/case-study-research-design-and-methods/oclc/50866947

Conflict of interest:

Authors declare not to have any conflict of interest.

Authors' contribution:

Eylin Jorge Coto and Angel Eustorgio Rivera designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, critically revised the article with important contributions to its intellectual content, reviewed the writing of the manuscript and approved the version finally submitted.

Eylin Jorge Coto was involved in data collection and elaboration of the draft.