Cooperativismo y Desarrollo, September-December 2019; 7(3): 290-312

Translated from the original in Spanish

Comparative analysis, business modality with focus of popular and solidarity economy, rural production associations

Análisis comparativo, modalidad empresarial con enfoque de economía popular y solidaria, asociaciones productivas rurales

Olga Patricia Zúñiga Brito1, Sonia Marisol Cajilima Mendoza2, Gliceria Gómez3

1Universidad Politécnica Salesiana. Ecuador. Email: olgazunigabrito@gmail.com

2Universidad Politécnica Salesiana. Ecuador. Email: scajilimam@est.ups.edu.ec

3Universidad Politécnica Salesiana. Ecuador. Email: gliceriapr@yahoo.es

Received: April 21st, 2019.

Accepted: August 31st, 2019.

ABSTRACT

Even though academia has advanced in conceptualization and there are policies on organizational forms with a solidarity economy approach, in the practice of rural environments, the behavior is heterogeneous in relation to the will for its impulse. There is not yet a clear systematization that contributes to the identification of regularities of this process. The objective of this work is to show the reality of two agricultural territories through a comparative analysis of the evolution of productive associations in the parishes of El Valle and San Joaquín, Cuenca canton, Ecuador. The characteristics of them are that the agricultural production is family and the surplus is destined for sale. The techniques applied for the collection of primary information were interviews with community actors and surveys of members, based on the use of the empirical method; the induction-deduction and historical-logical method that supports the theoretical-methodological analysis has been used. No details were obtained on the variables studied, but the findings obtained allow us to infer that, in El Valle, there is a greater level of organization in the performance of the productive associations and the integration of actors in comparison with the San Joaquin parish. However, the economic rates of the latter show better results, they have a direct sales channel, organized in the form of a distributor cooperative that is basically supplied by individual producers from other cities, therefore, it is an opportunity that the associations miss. The assumption about the irregularities present in the application of policies to promote this type of associations is corroborated.

Keywords: agricultural productive associations; Popular and Solidarity Economy; socio-economic indicators

RESUMEN

Aun cuando la academia ha avanzado en la conceptualización y existen políticas sobre formas organizativas con enfoque de economía solidaria, en la práctica de entornos rurales, el comportamiento es heterogéneo en relación con la voluntad para su impulso. Todavía no asoma una clara sistematización que tribute a la identificación de regularidades de este proceso. El objetivo de este trabajo es mostrar la realidad de dos territorios agrícolas a través del análisis comparativo de la evolución de asociaciones productivas de las parroquias El Valle y San Joaquín, cantón Cuenca, Ecuador. Estas se caracterizan porque la producción agrícola es familiar y se destina el excedente, a la venta. Las técnicas aplicadas para la recolección de información primaria fueron las entrevistas a actores de la comunidad y encuestas a los socios, sobre la base al empleo del método empírico; se ha empleado el método de inducción-deducción e histórico-lógico que soporta el análisis teórico-metodológico. No se obtuvo el detalle de las variables estudiadas, pero, los hallazgos obtenidos permiten inferir que, en El Valle, existe un mayor nivel de organización en el desempeño de las asociaciones productivas y la integración de actores en comparación con la parroquia San Joaquín, sin embargo, los índices económicos de esta última muestran mejores resultados, cuentan con un canal directo para la venta, organizado en forma de cooperativa distribuidora que se aprovisiona básicamente de productores individuales provenientes de otras ciudades, por ende, es una oportunidad que las asociaciones desaprovechan. Se corrobora el supuesto acerca de las irregularidades presentes en la aplicación de políticas para impulso de este tipo de asociaciones.

Palabras claves: asociaciones productivas agrícolas; Economía Popular y Solidaria; indicadores socio-económicos

INTRODUCTION

"Every real economy is a mixed economy, which can be presented as composed of three subsystems: the capitalist enterprise economy, the public economy and the popular economy" (Vázquez, 2010, p. 85). In this context, the solidarity economy appears as a consequence of the social inequalities that occurred during the revolutions of the 18th century (Ramírez Díaz, Herrera Ospina, & Londoño Franco, 2016). This model of economy has its roots in Europe, in the nineteenth century, when the market economy failed to achieve social harmony. The associationism of the working class was proposed as an alternative for the development and improvement of the living conditions of the population and was based on principles of solidarity (Da Ros, 2001); on the other hand, since the last quarter of the twentieth century, the Solidarity Economy has been developing a sense of belonging different from understanding the role of the economy and economic processes in contemporary societies (Askunze, 2013, p. 100). Daza (2018), expresses that: "Cooperativism becomes for farmers, peasants and communities a strategy of resilience to dispossession, provoked by agrarian modernization".

In response to the neoliberal model, this type of society is born with the purpose of ensuring reproduction, not through and through the accumulation of capital by the owners, but by taking care of the quality of life of its members (Coraggio, 2011); the need to recover the value of the collective, the democratic and the communitarian, not as an isolated situation of small business ventures, but as a system, an integration of actors and territories (Coraggio, 2018); to introduce solidarity in the economy (Razeto, 1999).

In Ecuador, the Popular and Solidarity Economy (EPS) sector from now on, for several years, was not considered part of the country's financial system, but a minority group in terms of handling financial actions and transactional amounts (Galarza Torres, García Aguilar, Ballesteros Trujillo, Cuenca Caraguay, & Fernández Lorenzo, 2017). Popular and solidarity economy is understood as the set of economic forms and practices, individual or collective, self-managed by their owners; in the case of being collective, they have simultaneously the quality of workers, suppliers, consumers or users of the same, privileging the human being, orienting good living, in harmony with nature, over profit and the accumulation of capital. MIES (2012), the EPS has been proposed as an economic-alternative model to the neoliberal capitalist model.

In this context, "Since 2011, through the Organic Law of Popular and Solidarity Economy (LOEPS), the EPS is recognized as a form of economic organization in which its members, either individually or collectively, organize and develop processes of production, exchange, marketing, financing and consumption of goods and services through relationships based on solidarity, cooperation and reciprocity, situating the human being as subject and end of its activity" (LOEPS, 2011 Art. 1); on the other hand, according to the LOEPS (2011), in its Article 4, it establishes the eight principles that will guide people and organizations; among these are: the search for Good Living and the Common Good and the priority of work over capital and of collective interests over individual interests.

In the same line of thought, according to the Superintendence of Popular and Solidarity Economy (SEPS) and the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (FLACSO): the EPS in the country evidences its role of economic and social inclusion, as well as its distributive and redistributive character. Jacome and others (2016), express that the redistribution of wealth is fairer and more equitable and within a framework of greater stability. In this area, Ecuador registers 8,154 EPS organizations, of which, in the real sector, there are 7,237 community organizations, associations, cooperatives and popular economic units; and, in the financial sector, 917 savings and credit cooperatives, community banks and savings banks (SEPS, 2015).

When considering agriculture from the perspective of associativity with an EPS approach, two dimensions must be taken into account: the first, from the traditional point of view, in which people cultivate only for their consumption, synonymous with profit; the second, from the economic point of view, as economic sustenance (Tacuri Orellana & Vásquez Salinas, 2015). Ecuador's agricultural productivity contributes an average of 8.5% to GDP, both economically and in terms of food security (UTN, 2017).

In Azuay, the composition of the EPS sectors is: 18 production cooperatives, 2 consumer cooperatives, 15 housing cooperatives, 61 savings and credit cooperatives and 118 service cooperatives (Torres Inga, 2013). The basis of solidary, community and participative production relations are the forms of organization that are established between the production process and the form of distribution of the benefits of the productive activity (González Burneo & Donestévez Sánchez, 2018).

The preliminary study carried out with the purpose of defining the problem, the object of research, showed that there is unequal development between the productive associations, located in the Parishes of San Joaquín and El Valle, which meant that the objective of the research was formulated around carrying out a comparative study between these associations, based on the analysis of their evolutionary process, through the analysis of selected indicators. The aim is to contribute to the systematization of best practices related to the performance of these organizations.

The parish El Valle is located in the southeastern part of the city of Cuenca, is one of the most important of the Canton, through its activities, harmonize and energize the main activities of the city in relation to productive associations. According to a study carried out by the Research Group of Medium and Small Enterprises (GIGMP), attached to the Salesian Polytechnic University (UPS), it was possible to highlight, among others, problems related to productive associations, lack of planning and collaboration between members. This constitutes barriers to face the competition of an undifferentiated market, in which agro-ecological products do not achieve positioning because they are not linked to segments aligned with responsible consumption (GIGMP, 2016). According to data presented in the Development Plan and Territorial Planning (PDOT) the parish El Valle has a percentage of 63.5% of the territory suitable for agriculture (Vintimilla Illescas, 2015).

Later, studies conducted by Jimbo and Araújo (2017) indicate that the agricultural associations of El Valle plan production, but in basic aspects such as sales, seasons and climatic conditions, which leaves aside factors that could provide greater benefits or profits such as planning by type of product, quantity, investment, etc. and indicates that the production planning, in the associations, can be improved, alternating sowing and harvesting of different types of products according to soil conditions and season, where each partner is dedicated to a specific crop, in order to avoid the repetitive supply already existing.

The San Joaquin parish is located 7 kilometers northwest of the city of Cuenca; it has an area of 185.1 square kilometers and a population of 5,126 inhabitants.

As a result of the bankruptcy of the Savings and Loan Cooperative" Coopera", ", the Production and Service Cooperative "Produciendo para Vivir Mejor" (PROGRASERVIV) is created, which means that, in San Joaquín, cooperativism moves vegetable producers. In this locality, there is a low presence of productive organizations in associative form; individual cultivation prevails. Regarding the agro-ecological and socioeconomic situation of producers, it has been determined that the income of the producer, along with his family, is 61.51 dollars per working day, per hectare cultivated, which is equivalent to $ 1,537.83 per month, which is enough to live comfortably, but limited savings or new investments (Sotamba Sanango & Sánchez Dumas, 2013). In this same area, 85.71% of communities, in the central part, plant vegetables and use their production, practically 100%, for sale Chilpe (Torres Inga, 2013), as well as horticultural production has generated employment and income for families, thus developing a productive system of welfare for families, despite environmental constraints and marketing problems (Tapia Barrera, 2014).

According to the above information, the perception of the researchers is that the parish of San Joaquin has had a greater dynamic of development, linked to the management of economic activities from agriculture.

The results corroborate this assumption, which shows that there are anomalies in the implementation of existing policies in the country, with respect to the alternatives used to generate development in these associations. It is not possible to identify regularities of these processes in these contexts; the actions in the territories are dispersed and atomized.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The type of research is qualitative-quantitative, the unit of analysis are the productive associations of the Parishes of El Valle and San Joaquín (Cuenca-Ecuador); the population selected for the study were the members of these associations. In order to gather primary information, the directors of both productive associations (MAG) and Parish (GAD) were interviewed. A survey was applied to the members of the seven associations of the Parish "El Valle" which is registered in the cadaster of the SEPS and MAG. The sample size, according to Random Unrestrictive Sampling (Malhotra, 2008) was calculated with a 95% confidence level and a margin of error of +/- 5%, which yielded a sample size equivalent to 87 surveys. The data in table 1 were used as a basis.

In the parish of San Joaquin we worked with the production Cooperative PROGRASERVIV, from which we could only collect data from 16 suppliers (due to limited access to information). Of these, 4 producers belong to San Joaquin, who supply vegetables and legumes; the rest of the products come from different parishes, cantons and provinces. The products are exhibited in the six points of sale of Gran Sol, also have direct distribution to educational centers, hotels, hospitals, wholesale sales, among others.

For data processing, IBM SPSS® (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 23 and Microsoft Excel were used; the analysis of results has a descriptive and correlational basis.

Table 1 - Cadastre of associations

PRODUCTIVE ASSOCIATIONS EL VALLE |

|

Control Entity |

Social role |

SEPS |

Association of agroecological producers Cruz del Despacho |

SEPS |

Association of agroecological producers Virgen del Rosario |

SEPS |

Association of agroecological producers Santa Martha |

SEPS y MAG |

Association of agroecological producers and smaller animals Virgen del Carmen |

MAG |

Association of agroecological producers San Pedro |

MAG |

Association of Entrepreneurs San Antonio de Gapal |

MAG |

Association of agroecological producers Señor de los Milagros |

PRODUCTIVE ASSOCIATIONS SAN JOAQUÍN |

|

Control Entity |

Social role |

SEPS |

Agricultural and livestock production and food service cooperative for better living "PROGRASERVIV" |

Source: Prepared by the authors from information from SEPS and MAG

As can be seen, there are three associations in the parish of San Joaquin, one of which is dairy producers, another refused to give information and the third is registered as a production cooperative, but is really dedicated to marketing, the results of which are included in the study. In the parish of El Valle, nine associations are registered, of which one is a livestock association, another refused to give information, and so we were able to work with seven of the productive associations. These were detailed in table 1 above.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results are presented in two sections; the first refers to surveys and the second to interviews.

In order to facilitate understanding, the results obtained by processing information through the application of surveys are organized in the following manner:

1. The variables that according to the analysis of the researchers allowed for establishing clearer differences between both parishes, these are indicators of quality of life (socio-demographic).

The availability of services is reflected in table 2.

Table 2 - Availability of Services (%)

Variables |

El Valle |

San Joaquín |

||

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Drinking water |

77 |

23 |

100 |

0 |

Electric power |

99 |

1 |

100 |

0 |

Telephone |

64 |

36 |

56 |

44 |

Sewer |

43 |

57 |

50 |

50 |

Internet |

57 |

43 |

75 |

25 |

TV |

72 |

28 |

81 |

19 |

Health |

45 |

55 |

69 |

31 |

Source: Prepared by the authors from results of statistical processing

As shown in table 2, the situation in terms of availability of services for people living in San Joaquin is more favorable, in relation to the availability of sewerage and TV; this difference is most notable in relation to the indicators of availability of health insurance and internet services, services that, in relation to the satisfaction pyramid, are at a higher level.

In relation to the availability of approximate per capita income per family, in El Valle parish, it is equivalent to $95.59; if compared to the amount of family income that could be obtained through secondary information from the small farmers of San Joaquin, shown above, they are far below.

In addition, it could be seen that another element that differentiates the performance between the parishes studied is the establishment of the price of the products; in the case of the partners of the parish El Valle, they are the ones who establish the same, according to the type of product; the opposite happens with the parish San Joaquin, that the price is negotiated with the marketer according to the weight and quantity of the product delivered. Having this association, which performs the functions of marketer, benefits the producers in relation to sales volume and deadlines, an opportunity that could also be taken advantage of by the producers associated with the Parish El Valle. This organization is especially supplied by producers who come from all over the province, who bear the costs of transportation, hence the lack of interest in getting closer to their sources of supply, bringing with them more participants to a market, which is shown in perfect competition, which displaces the participants who have fewer resources.

2. Variables, whose behavior was very similar and characterizes rural contexts of small producers in the country. The information is integrated into 3 groups of indicators, these are: productive indicators, contains available and planted land area, types of products and production, socio-economic indicators, represented by approximate monthly income and a third group of economic indicators that contains sales, percentage of monthly sales and sales expectations.

The area of land available for cultivation and the amount of land sown are shown in table 3.

Table 3 - Land area (m2)

|

<= 200 |

20,4% |

|

<= 100 |

21,4% |

201-600 |

21,4% |

101-200 |

22,3% |

||

601-1100 |

18,4% |

201-500 |

22,3% |

||

1101-4000 |

20,4% |

501-2000 |

17,5% |

||

4011+ |

19,4% |

2001+ |

16,5% |

Source: Prepared by the authors from results of statistical processing

The products that the members of the associations sow are shown in table 4.

Table 4 - Type of products (%)

Grains |

38,6 |

Vegetables and legumes |

40,9 |

fodder |

4,1 |

Potatoes and tubers |

9,4 |

Fruits |

7,0 |

Source: Prepared by the authors from results of statistical processing

As highlighted in table 4, producers in both parishes, in general, have a total land area between 200m2 and 1100m2 (60.2%), of which the majority, between 21.4% and 22.3% of the area is used for sowing products; of these, the products that are most cultivated are vegetables, vegetables and legumes in 40.9%, followed by grains in 38.6%, the rest of the land is used for potatoes and tubers, fodder that is used for raising animals and fruit, perform an average of 2 and a half harvests in the year, two types of products, which obviously results in a poor diversification in supply, concentrated mainly in vegetables, vegetables and legumes.

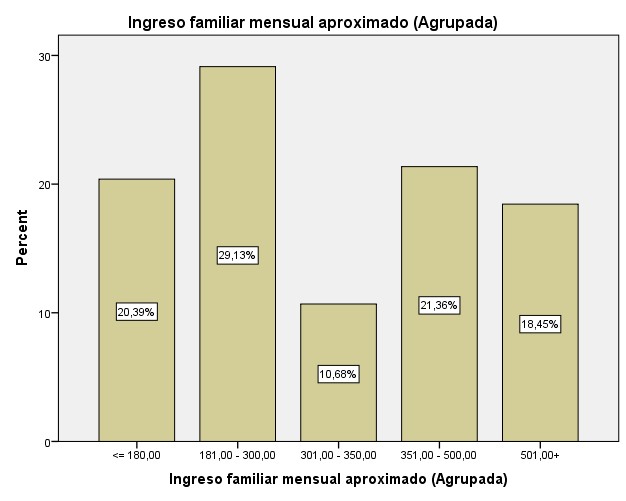

The description of household income is shown in graph 1.

Graph 1 - Description of family income

Source: Prepared by the authors from results of statistical processing

The average of the approximate monthly household income is $350 and the mode is $200, considered low in relation to the indices that indicate poverty in the country (below $84.39 as per capita income) (income comes from various sources). A Pearson correlation analysis was conducted between household income received and the amount of land sown, the index was r=0.35, meaning that there is a positive correlation; the correspondence analysis is reflected in graph 2.

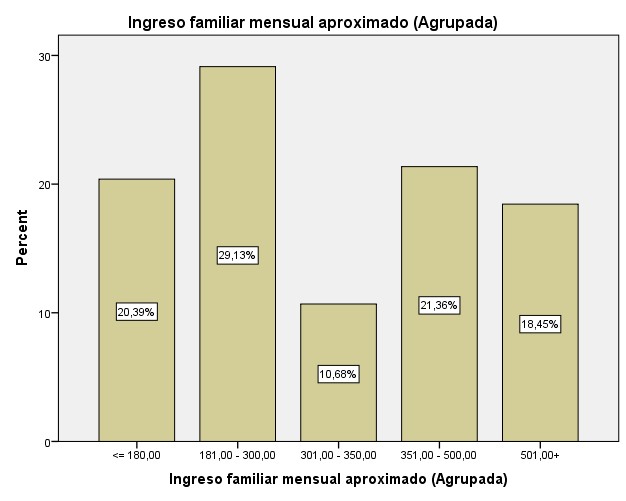

Graph 2 - Analysis of correlation

Source: Prepared by the authors from results of statistical processing

The correlation analysis model was used to demonstrate the relationship between the variables of amount of planted land area and approximate monthly family income of the parishes. Graph 2 shows that when the amount of land planted exceeds 2001 m2, the approximate monthly household income is greater than $500 and when the amount of land planted is <= 100 m2, the approximate monthly household income is <= $100. In other words, the greater the amount of land planted, the greater the income; it is true that the current income received, per household, is low. From this analysis, it is possible to induce several questions: why do not more resources go to sowing, do the income obtained go to other destinations, do not have alternative financing to allocate more resources to expand the sowing, which factors influence the decision of these people?, have much uncertainty most in relation to the benefit of working the land?

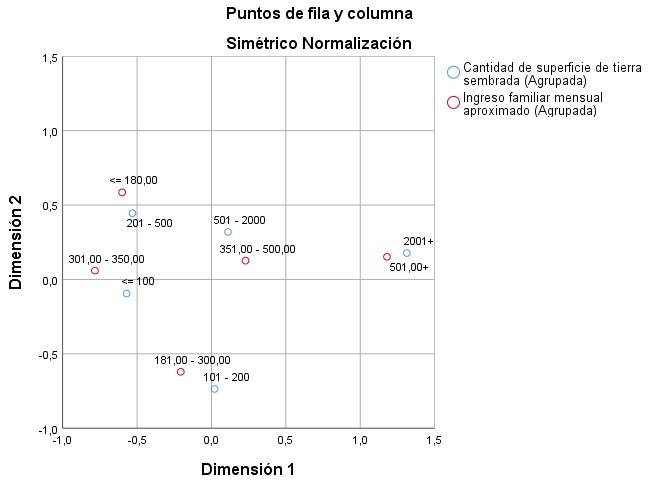

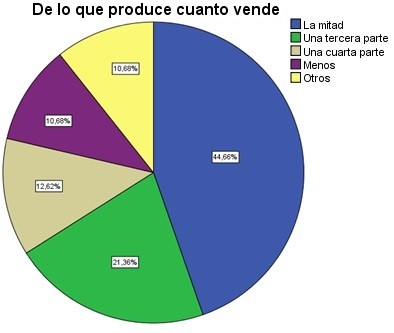

Graphs 3 and 4 show the quantity sold per product and the way it is marketed.

Graph 3 - Production

Source: Prepared by the authors from results of

statistical processing

Graph 4 - Sale

Source: Prepared by the authors from results of

statistical processing

The associated persons in 44.66% sell half of what they produce; 21.36% sell only the third part and 10.68% sell between 30%, 20% and some cases sell less than 10%. It can be generally deduced that, in the parishes studied, they plant an average of 25.78%, the production obtained from the land is marketed through the different points of sale. Most of the members of El Valle Parish sell their products in the market, the rest are sold through orders and, in some cases, attend fairs. The opposite occurs in the San Joaquin parish, where the different products are delivered directly to the PROGRASERVIV trading company according to the days established with the suppliers; these are small individual producers who pay taxes to the trading association.

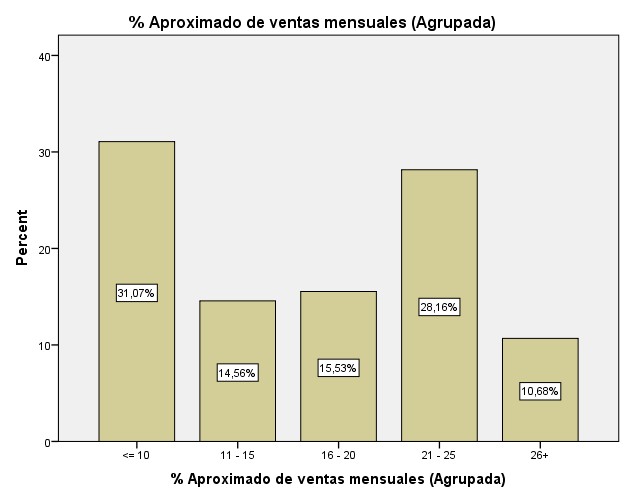

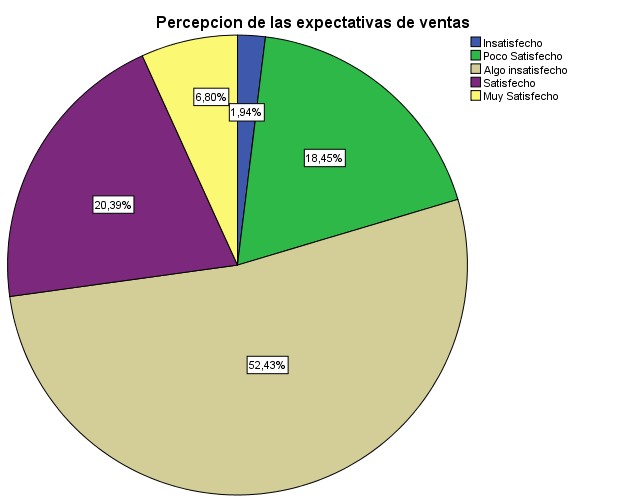

Graphs 5 and 6 reflect the approximate percentage of profit, corresponding to the level of monthly sales and the perception of the level of satisfaction with respect to their sales expectations.

Graph 5 - Analysis of sales

Source: Prepared by the authors from results of

statistical processing

Graph 6 - Perception of sales expectations

Source: Prepared by the authors from results of

statistical processing

It is observed that 31.07% of the families have the perception that the profit received from sales is less than 10% and 28.16% of the families perceive that the profits are between 21% and 25% of the sales made; however, the people surveyed in these two parishes, with respect to their sales expectations, do not feel very satisfied, only 6.80% express to be very satisfied. In some cases, they said that they were not able to sell all the products they put on the market and, on the other hand, it is observed that there is a low percentage of sown area with respect to availability. The correlation index between sown area and sales, in relation to what it produces, is (r = 0.011); the index (r = 0.166) rises a little in relation to sales expectations, but it is not significant; from this analysis it can be inferred that one of the greatest obstacles for these ventures to reach higher levels of productive yields is in marketing, an element that can even discourage their commitment to productive activity.

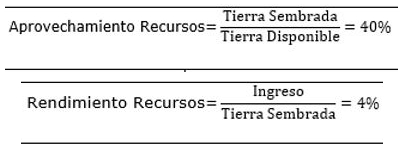

With the information obtained from the primary sources as a whole, considering both parishes, the following indicators were determined (Figure 1):

Fig. 1 - Calculation of efficiency indices

Source: Prepared by the authors from results of

statistical processing

The analysis shows that these associations take advantage of resources by 40%, according to the availability of land with a yield of 4%, this in relation to monthly income; the perception of income reaches low levels in relation to their sales prospects, which results in the marketing factor putting a brake on the development of these economic activities; it is possible to observe that the existing markets in the city offer large volumes of production, with a very repetitive supply. The large supermarkets that add value to the product compete with the city, through profit packaging and labelling, especially when it is an imported product.

On the other hand, it is clearly evident that there is production capacity that is not taken advantage of, even when the producers perceive that it is a good business opportunity for the profit it derives. There are, then, the reasons why the main problems are around marketing, as well as insufficient resources to increase sowings, uncertainty regarding the market, little knowledge of its needs based on determining segments and profiles, low use of productions in industrialization or improvement to provide greater benefits in marketing (packaging, labeling, etc.). Thought is linked only to primary production and the possibility of adding value to it is not considered, and even, being primary, orienting production towards other markets for which their competitive advantage is attractive, given that these products are mostly cultivated in the form of agro-ecological production.

3. Variables associated with El Valle parish. In this one, it was possible to extract more information, it is organized in 3 groups of indicators: productive indicators, it contains, levels of production obtained by each association, availability of animals and of breeding feet; indicators of efficiency, it contains, estimated cost by products, handling of animals, partners involved in the agricultural production; indicators of commercialization, it contains, place of sale of the products and ways of information to the market on the agro-ecological origin of the productions, considered as its competitive advantage and others such as: the significant that results for each member to be associated and the valuation of the sources of help.

Table 5 shows that the land sown is destined mainly for the production of grains and vegetables; the associations that stand out in the production of grains are: San Pedro (90%), Sr. de los Milagros and San Antonio de Gapal (81.8%), followed by Virgen del Carmen with (80%); in vegetables, San Pedro (90%), Cruz del Despacho (83.3%), San Antonio de Gapal (81.8%) and Santa Martha (64.7%).

Table 5 - Products shown in each association

Source: Prepared by the authors from results of statistical processing

Simultaneously with the agricultural activity, the partners, for the most part, dedicate themselves to the breeding of bigger and smaller animals, these with greater availability. In relation to the estimated cost, by type of product and animals, it was difficult to obtain the information due to the fact that, in general, they do not keep accounting records of production; therefore, 58% do not know the estimated cost of the products; however, according to the figures declared by the rest (42%), it is estimated that they incur an average monthly cost of $33.90. Some of the partners also have the sale of animals and animal products as a source of income. Similarly, it was difficult to obtain information on the estimated cost, due to the fact that 70% do not know it and, in some cases, do not sell; only 30% establish that the average cost is $75.58.

With respect to the number of members per family, which is involved in the production of the association, is reflected in table 6.

Table 6 - Members involved in the association

Family members involved in the production of the association |

Members involved |

Survey respondents |

Percentage (%) |

1 |

56 |

64 |

|

2 |

15 |

17 |

|

3 |

8 |

9 |

|

4 |

2 |

2 |

|

5 |

5 |

6 |

|

6 |

1 |

1 |

|

Total |

87 |

100 |

|

Source: Prepared by the authors from results of statistical processing

As can be seen in table 7, in most families, only one of its members is involved in the association, in almost all cases, women; men carry out other activities and children study; the causes can be several: low availability of arable land, low yields of these and, especially, the unprofitable agricultural activity, in these cases, which characterizes it as unattractive and reproducing high poverty rates. Young people do not feel motivated, which leads to the need to define policies that stimulate entrepreneurship in this area, especially by escalating production levels towards industrialization and commercialization to close production cycles.

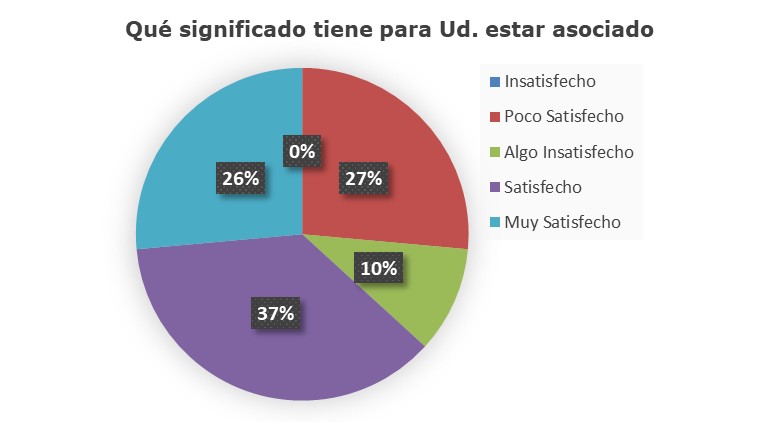

Graph 7 shows the significance of being associated for each of the partners.

Graph 7 - Meaning of being associated

Source: Prepared by the authors from results of

statistical processing

As shown, 37% of the partners say they are satisfied with belonging to an association; they see it as an opportunity to improve their economy and to work together with other partners; while 53% reach levels between little and dissatisfied; they express that the existing relationship between partners is not very good due to lack of organization and commitment, when it comes to carrying out planned activities.

Table 7 shows the appreciation of the partners with respect to the aid received from the different institutions.

Table 7 - Helps received, Parish El Valle (%)

Item |

Unsatisfied |

Not very satisfied |

Somewhat satisfied |

Satisfied |

Very satisfied |

Support received from government bodies and other institutions |

17 |

20 |

38 |

20 |

6 |

Assistance received by the GAD |

5 |

5 |

34 |

36 |

21 |

Help received by MAG |

21 |

11 |

37 |

18 |

13 |

Assistance received by financial institutions |

44 |

21 |

23 |

9 |

3 |

Source: Prepared by the authors from results of statistical processing

As can be seen, the levels of satisfaction with the help received from different governing bodies are low; hence the values are classified as few, satisfied and dissatisfied, between 10% and 65%; the help received by the parish GAD reaches the highest levels of satisfaction. This is the institution that manages the budgets assigned to the associations, but in general these aids are atomized depending on specific requirements, the project is not yet defined as the ideal way to integrate demands and budget needs to meet a specific objective for the organizational strengthening of these associations. They do not take advantage of opportunities on the part of the MAG, whose offer is especially linked to technical aids. However, 91% of the members state that they receive aid through training and 87% receive aid through seeds. With respect to the aid received by the financial institutions, the partners feel dissatisfied, because they are demanding for the granting of credit; in some cases, small producers consider the interest high and prefer not to ask for money. Nor do these institutions provide information and training for these people whose level of education, in general, is low; on the other hand, the low attitude of commitment to collaboration denies the possibility of alliances between partners as a strength to access credit applications; in the least of cases, they have a common fund that serves as a benefit for all members, should they require help.

Agroecological production is the competitive advantage of this type of productive associations; however, the partners do not correctly distinguish which are the attributes they could handle around making this benefit known; most indicate that the way to distinguish agroecological production is through the type of natural fertilizer they use for sowing their products; but they do not know how to handle communication for buyers; some express that consumers do not recognize this type of agriculture as a benefit because, in general, the products are small due to the absence of the use of chemicals in sowing and product growth.

They say they know the approach of the Popular and Solidarity Economy; they hear about it in meetings, trainings and, in some cases, on the radio.

In relation to the factors linked to associativity, it is the Santa Martha association that has the highest percentage of associated family members (16.5%); of these, (70.6%) mentions being somewhat dissatisfied in their sales, data that may be related to the fact that only between 21-25 percent of their monthly production is marketed monthly. Virgen del Rosario has a (15.53%) of associates; of them, 43.8% say they are somewhat dissatisfied, 50% sell between 16-20% of their production.

4. Variables associated with the San Joaquin Parish were considered indicators of perception of associativity, such as, help received from financial institutions, frequency of delivery of products to the marketer and their desire to belong or not to an association.

The surveyed individual producers of San Joaquin are considered somewhat dissatisfied with their sales since 56.3% express that they only manage to sell between 21-25 percent of their monthly production.

Table 8 shows the appreciation of the members with respect to the aid received from financial institutions.

Table 8 - Help received, Parish San Joaquín (%)

Item |

Unsatisfied |

Not very satisfied |

Somewhat satisfied |

satisfied |

Very satisfied |

Assistance received by financial institutions |

13 |

13 |

25 |

19 |

31 |

Source: Prepared by the authors from results of statistical processing

As can be seen, 50% members of Parish San Joaquin are satisfied with the help received from the financial institutions; take into account that these people have a greater level of incomes, and so they are more attractive to receive As can be seen, 50% of the members of the San Joaquin parish are satisfied with the aid received by financial institutions; note that these people have a higher level of income and are therefore more attractive for credit. Also, it could be determined that some of the providers are interested in associating because they see it as an opportunity to work in a team, receive benefits and training from the different entities; while another majority (70%) indicates that they are not interested in belonging to any association because they lack time to attend meetings and training, prefer to work independently and thus avoid inconveniences.

The analysis of the interviews conducted resulted in the following:

In the parish El Valle, the MAG promotes training through theoretical and practical workshops, the fulfillment of objectives is controlled through monitoring of crops, and the parish GAD provides assistance for the implementation of agro-productive projects. They also expressed that the main problems present in the associations are related to management, due to the lack of interest and responsibility on the part of its members, also the limited leadership capacity and the lack of commitment to put into practice what they have learned. As for the difficulties presented by the association directors, at the moment of leading the association, there is a lack of communication, time and coordination among the members of the associations. They present problems in terms of the lack of participation and companionship when it comes to making their products known in the market, since for the sale of products, which are exhibited in the market, on Saturdays, they alternate between the members of each of the associations.

From the results of the research, it can be concluded that:

From the theoretical perspective, the popular and solidarity economy arises from the need to improve people's quality of life, in order to develop production and commercialization processes, promoting activities of small and medium associative economic entities in order, in this way, to revive the demand for goods and services; the main thing in this approach is the prevalence of work over capital, based on principles of collaboration and solidarity.

The productive associations of agricultural base lack informative support and their organizational level is low, which affects their functioning as economic organizations for decision making; they also limit access for the development of studies, which can contribute to the identification of regularities in this area and to the generalization of good practices. This hinders the structuring of territories that function as systems under the principles of the social and solidarity economy, promoting development in the face of the reality of neoliberal models.

For the reasons given, it was not possible to make a detailed comparison between the productive associations belonging to both parishes (SEPS only records statistics on cooperatives in the financial sector, segments 1 and 2; in the case of Parroquia San Joaquín, there was access to one of the two associations and, to a limited extent, of a marketing type). This constitutes a limitation for the investigation, since the comparative analysis could only be carried out on some factors that, in general, are influencing both territories.

However, some data, which could be considered as preliminary information, show interesting results, such as the fact that the San Joaquín parish has evolved faster in comparison with the El Valle parish, in terms of socioeconomic indicators, which is basically sustained in small individual producers and have only two associations linked to the EPS. It is inferred that, here, individual production, organized in small vegetable gardens and associations that are not registered in the MAG and SEPS cadastres, are having better results, even though the results achieved, as evidenced in the report, are below their expectations. The following question could then be asked: are the postulates that the popular and solidarity economy could be a way of development for rural territories not being fulfilled?

One answer could be linked to the fact that they are better organized for commercialization or that they have found opportunities, from channels that link them directly with markets, an element that constitutes a point of analysis for future research; they also have greater quantity and quality of natural resources. In the Valley, the resources are limited and the producers are more affected by the lack of water, although the current report and the antecedents affirm that one of the essential points to make grow the productions of these organizations is in the commercialization.

The intermediary association of San Joaquín, dedicated to the commercialization of agroecological products, sells more products from other associations than from that territory; in fact, the products it sells, from this parish, come from small individual producers; in such a way that having a channel for the distribution of its products, this opportunity is wasted on the part of the associations belonging to both parishes; even though it is stated that, in the field of EPS, it is pertinent to promote the direct sale of the products. In this context, producers do not organize themselves adequately, the presence of producers at fairs is not systematized and, even, they do not reach an agreement among themselves to produce a greater variety of products or lower distribution costs. The alternative of intermediation is more effective, especially when it is organized under the principles of solidarity; even so, the expectations of sale, in both cases, are low, which evidences potentialities that, if properly channeled, can positively influence the low levels of use of existing lands, with the consequent positive impact on the quality of life of the families.

The competition of agricultural products is perfect; This means that the organizational forms linked to these sectors basically depend on accepting prices, as long as there are no clear policies on the part of the state to encourage value contributions to them, in terms of completing production cycles, expanding industrial production lines, market preparation of these products to compete with supermarkets and/or position these products for their advantage as agroecological production, simultaneously with the awareness of consumers in betting on achieving harmony in coexistence with the environment, it will be difficult to achieve that these territories can be aligned with a real development strategy.

There is a greater level of organization in the parish of El Valle in terms of productive associations and integration. Between these and the GAD, given that access to information was much easier, there is a greater number of associates. They function in accordance with the law with respect to organizational structure and performance of functions by their members. It should be noted that the Salesian Polytechnic University a has been developing an organizational strengthening project for the last two years, which has contributed to the improvement of its performance indicators; in San Joaquín, the producers, for the most part, are not associated, although some of them, until 2012, belonged to the Saving and Credit Cooperative "Coopera".

In the analysis of socioeconomic variables, San Joaquin producers have advantages, which is consistent because these people receive a higher level of monthly income. In relation to the production variables, the situation is similar in both parishes; the structure of land availability behaves in a similar way, approximately 20% distributed in the ranges of 200 to 4000 m2, as well as the areas sown in equal % and ranges. The owners of land, with sown areas greater than 2,000 m2, are in the parish of San Joaquin (68.8%), without belonging to any association.

Efficiency indicators show a very low level of use of available resources, which leads to the study of the reasons behind these results and the formulation of policies to support producers in the parishes.

The financial support is poor, it is observed that the producers of San Joaquin have achieved greater benefits, above all, with credit lines; they offer less risks for the financial institutions, due to their economic availability.

In view of these results it is recommended:

To the associations of the Parish El Valle: study the possibility of linking up with the Comercializadora PROGRASERVIV which, being an EPS association, maintains policies and alternatives that favor agricultural producers. Value other alternatives for marketing their products, privileging the direct channel, which could be possible with institutions or companies.

To the GAD of the San Joaquin parish: to stimulate the link of the producers to the commercializing PROGRASERVIV, since this one supplies basically of producers of other regions. To influence the members of the association in the territory so that they are more receptive in providing information that pays tribute to studies of this nature.

To the Government: to define policies that generate alternative marketing channels for these producers, especially the associations that the study shows, that for various reasons their indicators are lower; that stimulate creativity to promote ways of contributing value to these products and can have a better positioning in the market; that make visible the competitive advantage in favor of agroecological production.

In general, it is recommended to continue the studies related to the topic, in order to cover the limitations presented in this research and to answer the questions that it has generated.

REFERENCES

Askunze, C. (2013). Más allá del capitalismo: alternativas desde la Economía Solidaria. Documentación social, (168), 91-116.

Coraggio, J. L. (2011). Economía Social y Solidaria. El trabajo antes que el capital. Quito: Ediciones Abya-Yala. Recuperado a partir de http://www.socioeco.org/bdf_fiche-document-652_es.html

Coraggio, J. L. (2018). Potenciar la Economía Popular Solidaria: una respuesta al neoliberalismo. Otra Economía, 11(20), 4-18.

Da Ros, G. (2001). Realidad y desafíos de la economía solidaria: iniciativas comunitarias y cooperativas en el Ecuador. Quito: Ediciones Abya-Yala. Recuperado a partir de https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abya_yala/394

Daza, E. (2018). Desarrollo rural y cooperativismo agrario en Ecuador. Eutopía, Revista de Desarrollo Económico Territorial, (13), 177-180. https://doi.org/10.17141/eutopia.13.2018.3476

Galarza Torres, S. P., García Aguilar, J. del C., Ballesteros Trujillo, L., Cuenca Caraguay, V. E., & Fernández Lorenzo, A. (2017). Estructura organizacional y estilos de liderazgo en Cooperativas de Ahorro y Crédito de Pichincha. Cooperativismo y Desarrollo, 5(1), 19-31.

GIGMP. (2016). Informe diagnóstico socioeconómico de las asociaciones de la parroquia El Valle. Cuenca: Grupo de Investigación de Medianas y Pequeñas Empresas.

González Burneo, V. F., & Donestévez Sánchez, G. M. (2018). Sistemas de relaciones de producción de participación social y comunitaria como base del desarrollo sustentable. Cooperativismo y Desarrollo, 6(2), 125-140.

Jácome, H., Sánchez, J., Oleas, J., Martínez, D., Torresano, D., & Romero, D. (2016). Economía solidaria. Historias y prácticas de su fortalecimiento. Quito: Superintendencia de Economía Popular y Solidaria.

Jimbo, G. A., & Araújo, G. I. (2017). Análisis de gestión de producción agrícola en asociaciones constituidas por el MAGAP, parroquia El Valle, Cuenca Ecuador. Cuenca: Universidad Politécnica Salesiana.

LOEPS. (2011). Ley Orgánica de Economía Popular y Solidaria. Superintendencia de Economía Popular y Solidaria.

Malhotra, N. K. (2008). Investigación de mercados (5.a ed.). Naucalpan de Juárez: Pearson Education. Recuperado a partir de https://www.biblio.uade.edu.ar/client/es_ES/biblioteca/search/detailnonmodal/ent:$002f$002fSD_ILS$002f0$002fSD_ILS:311870/ada?qu=INTERNET&ic=true&ps=300

MIES. (2012). La economía popular y solidaria. Ministerio de Inclusión Económica y Social.

Ramírez Díaz, L. F., Herrera Ospina, J. de J., & Londoño Franco, L. F. (2016). El Cooperativismo y la Economía Solidaria: Génesis e Historia. Cooperativismo & Desarrollo, 24(109). https://doi.org/10.16925/co.v24i109.1507

Razeto, L. (1999). Economía Solidaria: concepto, realidad y proyecto. Persona y Sociedad, 13(2).

SEPS. (2015). Qué es la Economía Popular y Solidaria (EPS). Recuperado 18 de septiembre de 2019, a partir de http://www.seps.gob.ec/noticia?que-es-la-economia-popular-y-solidaria-eps-

Sotamba Sanango, R. P., & Sánchez Dumas, J. S. (2013). Estudio de comercialización hortícola en la parroquia San Joaquín Bajo - Cuenca (Diploma en Ingeniería Comercial). Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, Ecuador. Recuperado a partir de http://dspace.ups.edu.ec/handle/123456789/5552

Tacuri Orellana, K. A., & Vásquez Salinas, E. N. (2015). Análisis de los planes estratégicos del sector agrícola en la ciudad de Cuenca y elaboración de un plan estratégico para APA Azuay (Asociación de Productores Agroecológicos del Azuay) mediante la aplicación de un cuadro de mando integral para el período 2014-2015 (Diploma en Ingeniería Comercial). Universidad de Cuenca, Cuenca. Recuperado a partir de http://dspace.ucuenca.edu.ec/handle/123456789/22841

Tapia Barrera, M. R. (2014). Prácticas y saberes ancestrales de los agricultores de San Joaquín (Maestría en Agroecología Tropical Andina). Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, Ecuador. Recuperado a partir de http://dspace.ups.edu.ec/handle/123456789/6297

Torres Inga, C. S. (2013). El estado de las finanzas solidarias en la ciudad de Cuenca (Maestría en Desarrollo Local Mención en Población y Territorio). Universidad de Cuenca, Cuenca. Recuperado a partir de http://dspace.ucuenca.edu.ec/handle/123456789/4779

UTN. (2017). La Importancia de la Agricultura en nuestro país. Recuperado 18 de septiembre de 2019, a partir de https://www.utn.edu.ec/ficaya/carreras/agropecuaria/?p=1091

Vázquez, G. (2010). La sostenibilidad de los emprendimientos asociativos de trabajadores autogestionados. Perspectivas y aportes conceptuales desde América Latina (Maestría en Economía Social). Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento, Buenos Aires. Recuperado a partir de http://www.academia.edu/12735367

Vintimilla Illescas, B. C. (2015). Potencial turístico de la parroquia El Valle, del cantón Cuenca (Diploma en Ingeniería en Turismo). Universidad de Cuenca, Cuenca. Recuperado a partir de http://dspace.ucuenca.edu.ec/handle/123456789/22368